Reflections from 2024

Reflections on a life in Art, Design and Media and pointers to the 21st century zeitgeist

OK, I was born in November 1945, some six months after the end of World War 2, But this isn't going to be an autobiography. I want to tell you about how I discovered that I wanted to be an artist, what I studied and read, and how I got to be a participant in the Creative Industries, with various adventures as an audio-visual designer, illustrator, and graphic designer in the 1970s, and just at a time (in the 1980s and 1990s) when the entire industry - from Print to Broadcast, and Telecoms to Design was rapidly transforming to the Digital domain.

After the 1980s the computerised media gained ascendancy - slowly at first with expensive paintbox machines like the Quantel, and later the Spaceward and Silicon Graphics workstations, then typesetting and page-make-up dedicated mini-computers, then of course the Personal Computer, initially with a command-line interface like MS-DOS, then thankfully the graphical-user-interface on the Liza (1983) and the hugely popular Macintosh (1984), stemming ultimately from Alan Kay's work on the Xerox Alto (1973) - but this was still a decade or so away for me at Art school.

I had a talent for 'drawing' - the kind of neo-realistic figurative drawing that at that time in art college was called 'objective drawing', ( as if!) - (another kind of drawing, that strangely wasn't encouraged then at my art college, you could call 'expressionist' drawing - a freer, more idiosyncratic style of drawing, based loosely on 'objective' reality. - Exactly what 'objective' means in this context was never examined philosophically - I didn't discover anything about the mechanics of vision, nor the theories of perception and cognition at college, nor much of any theories of consciousness either, but I was a keen autodidact, and loved libraries, and scouring second-hand book stores, and avidly scanning magazines like New Scientist and Scientific American; art journals like Studio International and Leonardo; and new-wave sci-fi like New Worlds Speculative Fiction. One of the books that really turned me on at this time (mid 1960s, when I was at Portsmouth Art College) was by the St Martins Art College historian Aaron Scharf (Aaron Scharf: Art and Photography 1965)

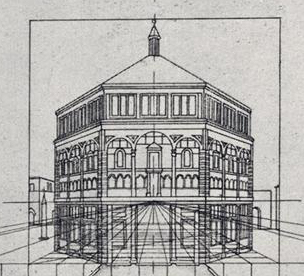

and got me really interested in the technology of representation, in a chain of logic that included the fumbling but beautiful attempts at the pre-mathematical understanding of 'things seem to get smaller the further away they are' (intuitive perspective) early attempts at perspective for example by Ucello, and Fra Angelico:

and got me really interested in the technology of representation, in a chain of logic that included the fumbling but beautiful attempts at the pre-mathematical understanding of 'things seem to get smaller the further away they are' (intuitive perspective) early attempts at perspective for example by Ucello, and Fra Angelico:

Paolo Uccello's Corpus Domini predella (c. 1465–1468)

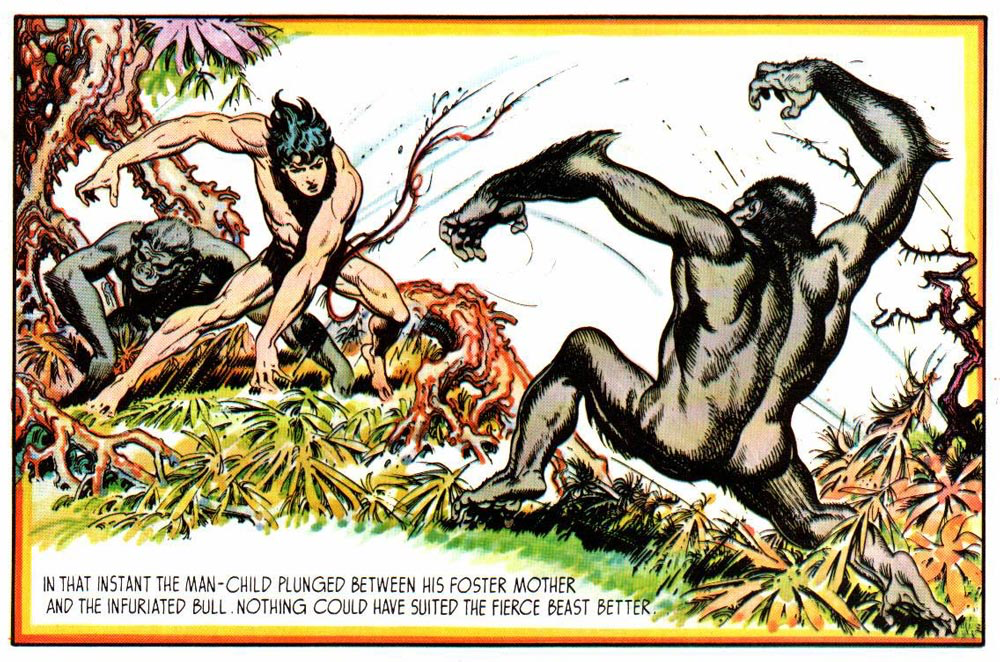

And it was Scharf's Art and Photography that really awakened what was to be a lifelong fascination with Art and Technology a trail that took me through print-making to illustration and especially to comic-strips and animation - those mass-reproduced art-forms that weren't on the usual art college curriculum in the early Sixties. It was later that I discovered the great NY School of Visual Arts - formerly the Cartoonists and Illustrators School - founded in 1947 by the consummate Tarzan artist, Burne Hogarth:

Burne Hogarth was one of the central artists in the 'golden age' of comic-illustration in the 1930s, as I noted in my mediainspiratorium: "In many ways, this is a golden age for the narrative comic-strip and several masters of the art emerge or become well-known in the 1930s, including Chester Gould (Dick Tracy), Al Capp (Lil Abner), Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon, Rip Kirby), Hal Foster (Prince Valiant), Burne Hogarth (Tarzan), and Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates). Not to mention Bob Kane’s Batman and Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman! Why? In an era before television, comics were a low cost visual-narrative entertainment – less demanding than novels, geared for those recent American immigrants still struggling with English, colourful and addictive like a radio soap-opera."

But to review this history - from the Western discovery of linear perspective onwards:

Fra Angelico: Annunciation frescos (1440-1445)

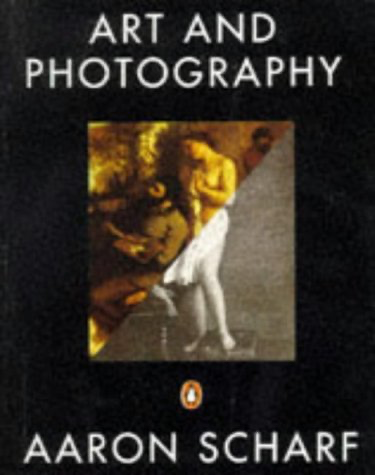

these early Renaissance experiments derive from much earlier Arabic discovery of perspective: from Ibn Al Haithan (aka Alhazen) - his seven volume Book of Optics (Kitab al-Manazer made as early as 1021 AD)

from Alhazen Book of Optics 1021

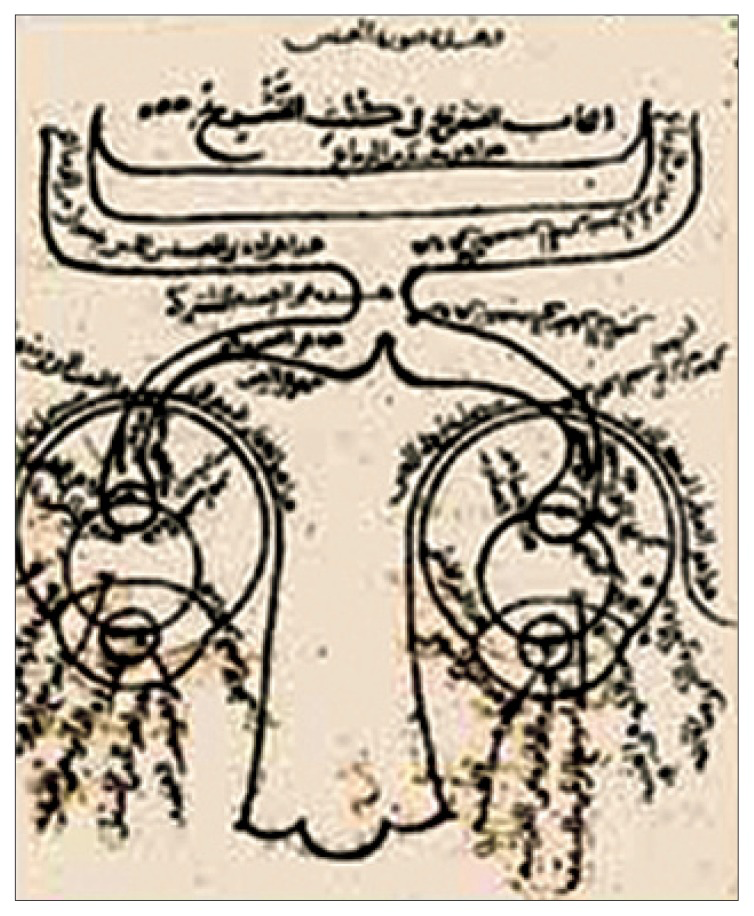

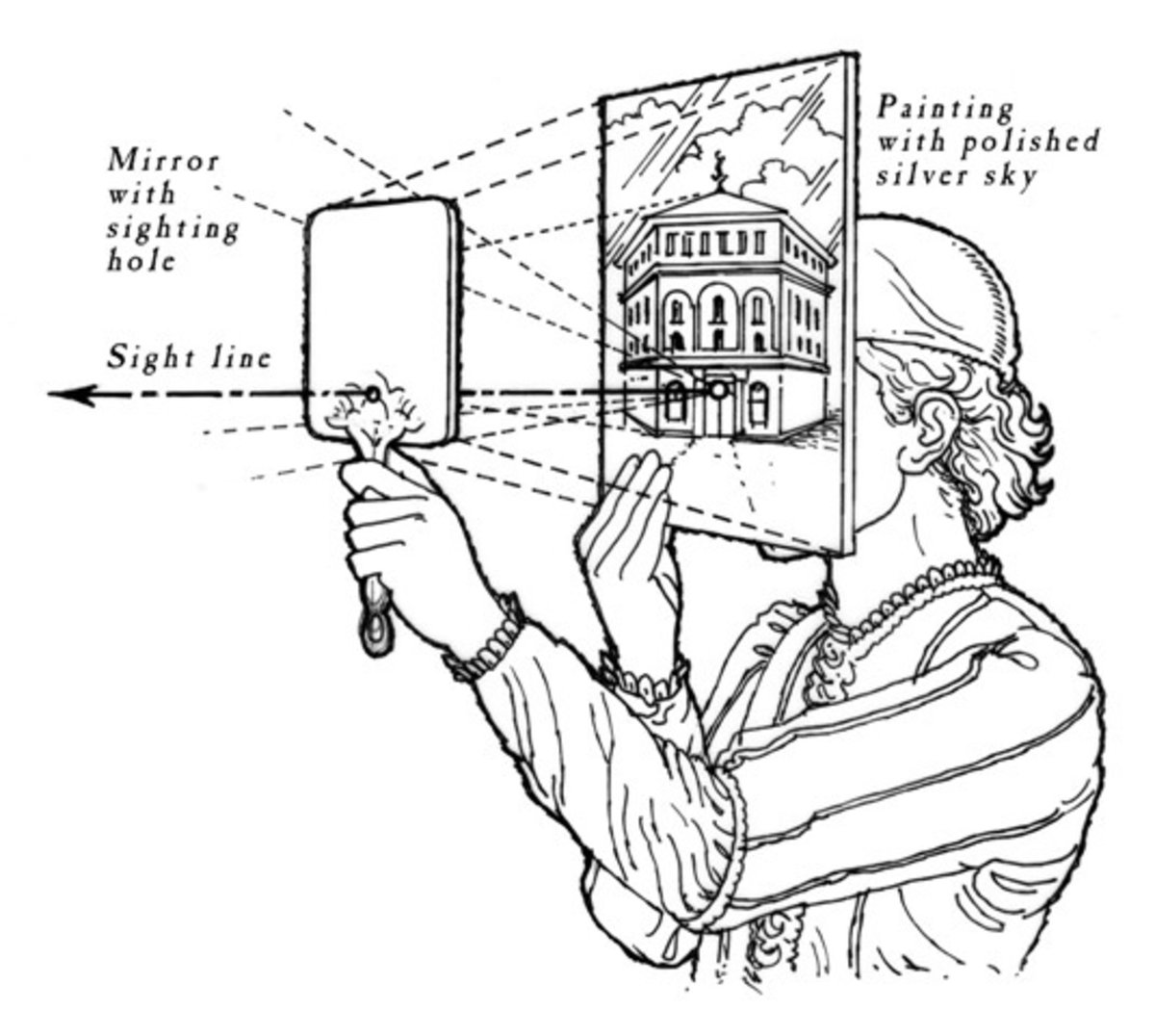

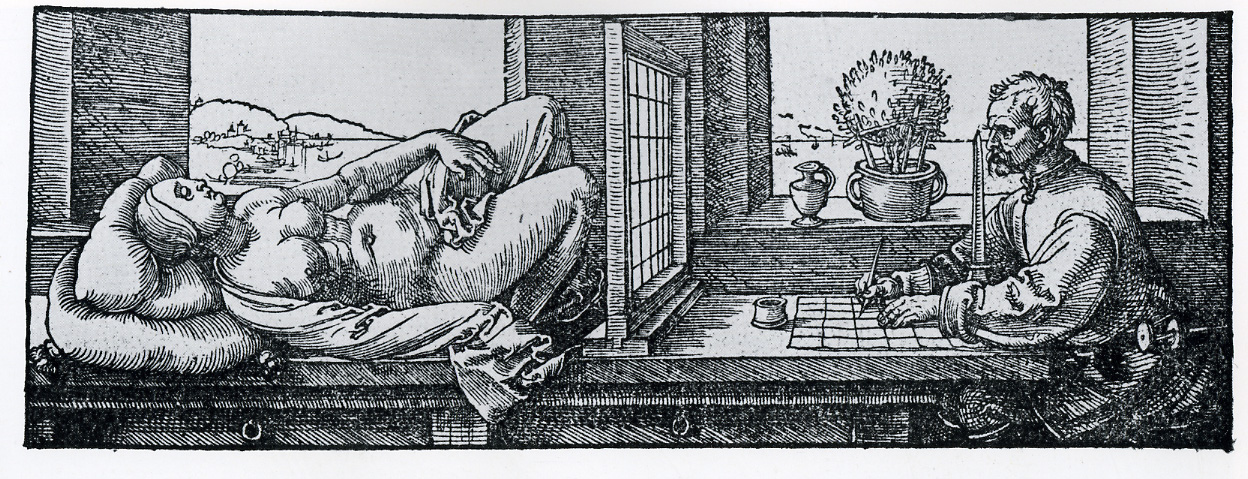

through the rediscovery of Alhazen and mathematical refinements of Alberti and Brunelleschi in the Renaissance, then Albrecht Durer's wonderful perspective machines and drawings,

Brunelleschi: silvered mirror perspective experiment c1415

Brunelleschi: silvered mirror perspective experiment c1415

Diagram based on Filippo Brunelleschi Theory of Perspective c1415

Diagram based on Filippo Brunelleschi Theory of Perspective c1415

Albrecht Durer: Perspective Machine c1525

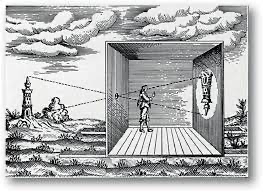

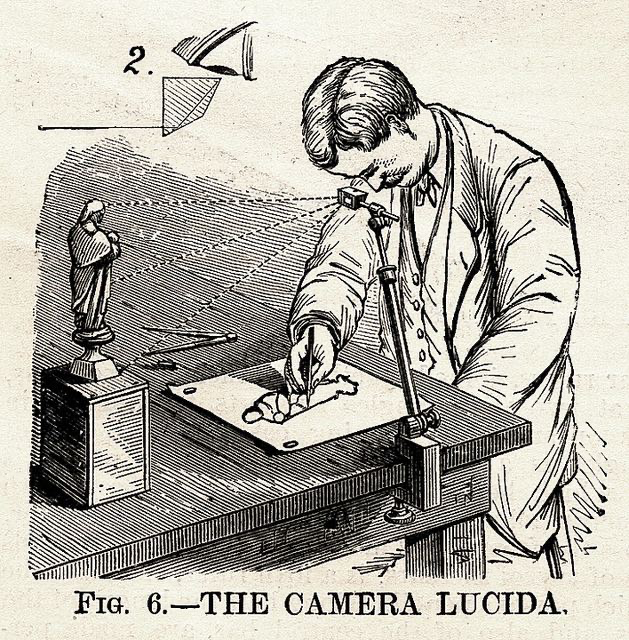

the invention of the camera obscura, and a few centuries later, the camera lucida (Hyde Wollaston 1806),

Camera Obscura (antiquity)

Wollaston: Camera Lucida 1816

then Johann Schulze's discovery that silver nitrate darkened on exposure to light (1719), and Wedgwood's late 18th century experiments with photography.

Thimas Wedgwood: photogram on leather c1800 pre-fixative

In the 19th century, the race to perfect photography involved Joseph Niépce (using bituman of Judea, which was hardened by exposure to the Sun), then Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and the spectacular success of the Daguerreotype (from 1839), then William Henry Fox Talbot's even more successful negative-positive Calotype (1839/1840) - but I've covered these photo-related topics quite thoroughly in my mediainspiratorium,

https://mediainspiratorium.com/1800-1920/

so I'll continue my experiences with Art and Technology with the first way that audio-visual art impacted on me directly. This derived from various projection techniques used with live or recorded music and sound - from 1940s and 1950s experiments by counter-culture pioneers like Harry Everett Smith. I entered this field in in 1967, when me and my close contemporaries were preparing our degree shows at Portsmouth College of Art. A group of us (Gary Crossley, Bob Blagden and myself), much influenced by the polymathic visiting lecturer John Bowstead, an early pop-artist-painter, Young Contemporary and ex Slade School, who had been evangelising light-shows as an expansion of art (Bowstead had co-founded the Hornsey Light/Sound Workshop in 1962), we had decided on orchestrating a multimedia show of our own as a kind of fringe degree show. Our heads were filled with early pop-art, a predilection for Rauschenberg and Paolozzi and Hamilton - all three mixing repro-technologies and fine art media like painting - to produce art that celebrated the fusion of art and technology, and we enthusiastically read sci-fi, the writings of Marshall McLuhan and his 'extensions of man' - the various new media we were busy inventing, So we decided to mix an 8mm film, two Carousel slide-projectors (using 35mm colour slides), an Aldis Projector, using two and a quarter-inch colour slides, and an old stereo reel-to-reel audio tape recorder to manage our sound-track, so our show, which we titled Krystal Klear in Warp Drive (in homage to Tom Wolfe, Star Trek and sci-fi books and comics generally). We filmed live TV broadcasts of NASA Atlas and Saturn launches, the Ronettes Walking in the Rain - a multimedia sound-mix in itself,

Ronettes Walking in the Rain 1964

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tBBys5TLxCI

and news-clips of relevant stuff, mixed-in with slides of comic-book imagery, Amazing Sci-Fi images, Marvel comics, and we presented all of this in a multi-screen, multimedia, light-show with loud music-based/newsreels sound-track installation - and got a favourable reception from none other than the art historian George Knox - who sat there with his mouth open. We were pleased with Krystal Klear, but it was amazingly crude and ad-hoc compared with stuff we did later - but it was multimedia, multiscreen - an attempt to materialise this zeitgeist - still an underpinning major theme in Modernist art. So audio-visual work became a subject of study, just as the underground began to emerge publicly in the mid 1960s, with regular 'light-shows' at Hoppy Hopkins and Joe Boyd's UFO club in Tottenham Court Rd in 1965 - and at the spectacular 14-Hour Technicolour Dream at Alexandra Palace in 1966.

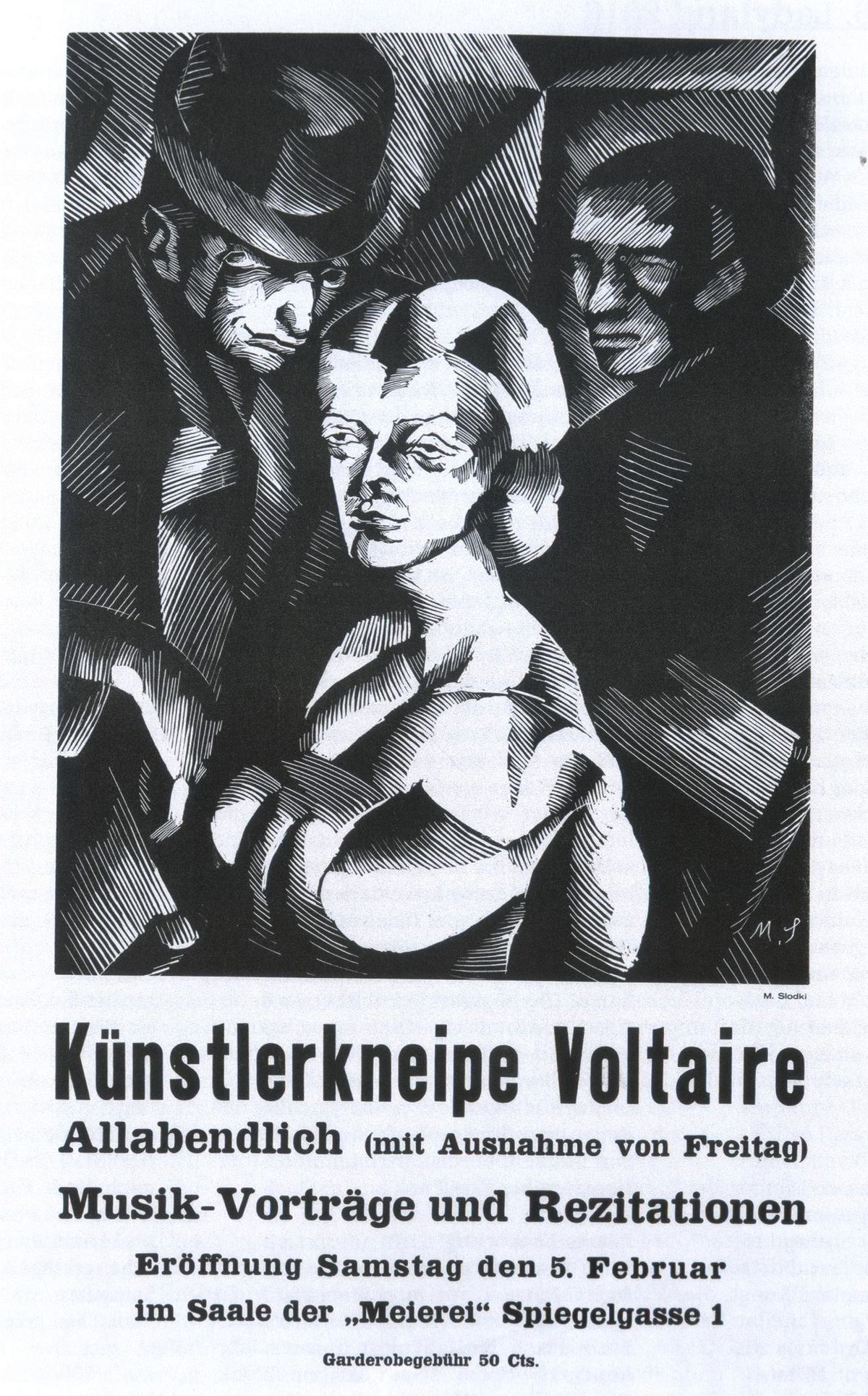

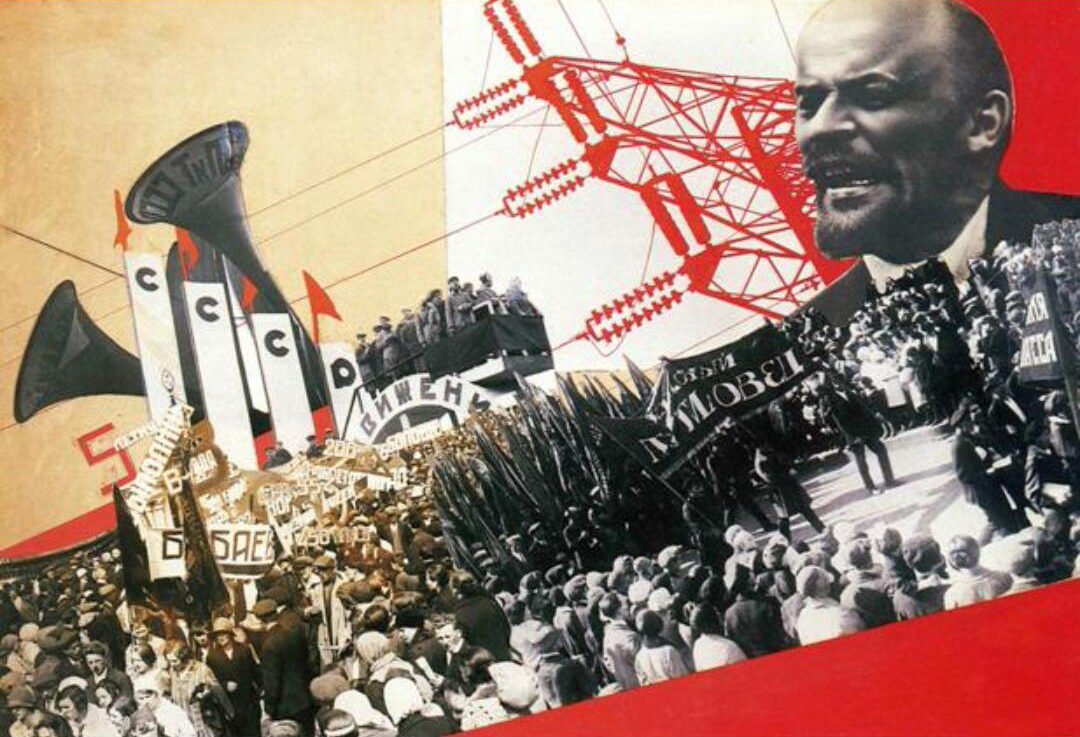

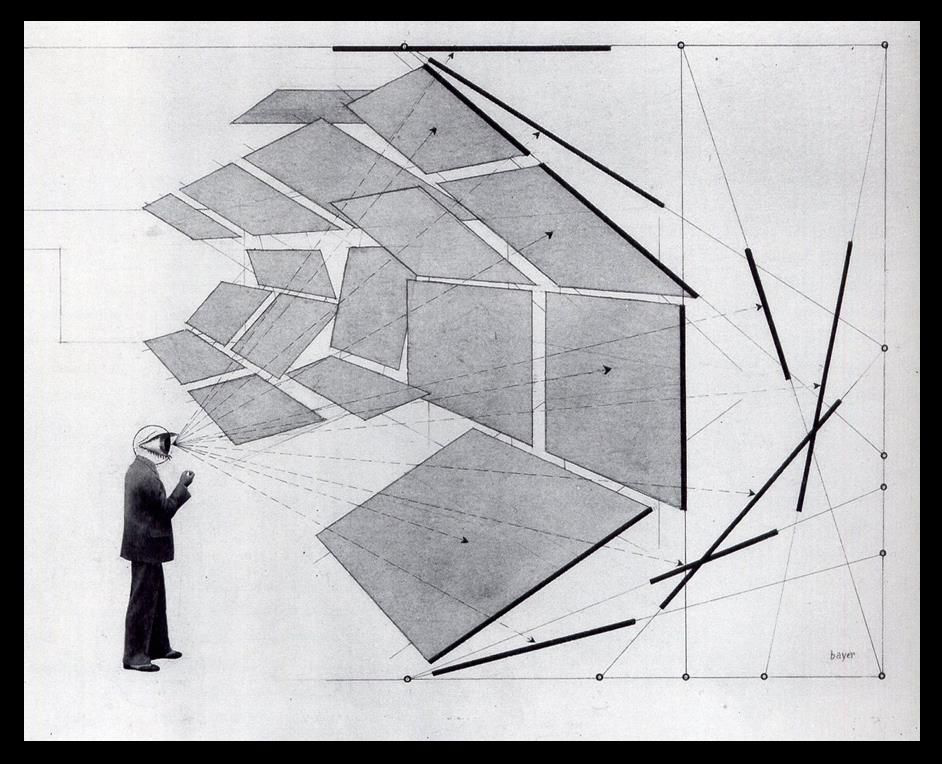

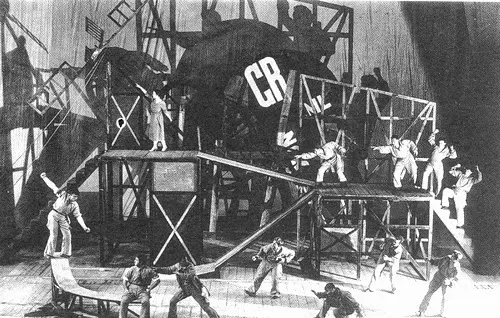

So Krystal Klear was my first adventure in what was then called Audio-Visual Art - a label that embraced Light Shows - and twenty years before MTV and the 'pop-video'. It was this fusion of art and technology that led me to write my degree-essay on the Gesamtkinstwerk (the composite art-work) and to explore the history of son et lumiere, theatre-design, stage-design, simulation-rides, multimedia exhibitions and displays - from the 1900 Paris Exposition (Photorama, Mareorama etc), the Ballets Russes productions of Diaghilev, Gordon Craig's modernist, minimalist, dramatic designs for theatre productions, through Dada Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich and Club Dada in Berling, to the Russian Constructivist displays of Popova, Klucis, Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, to Bauhaus theatre stuff by Herbert Bayer, Oskar Schlemmer and others - illustrated below:

Lubov Popova: Stage set for Meyerhold's Earth on Turmoil 1923

Lubov Popova: Stage set for Meyerhold's Earth on Turmoil 1923

Serge Diaghilev and Leon Bakst - stage design for The Firebird 1923

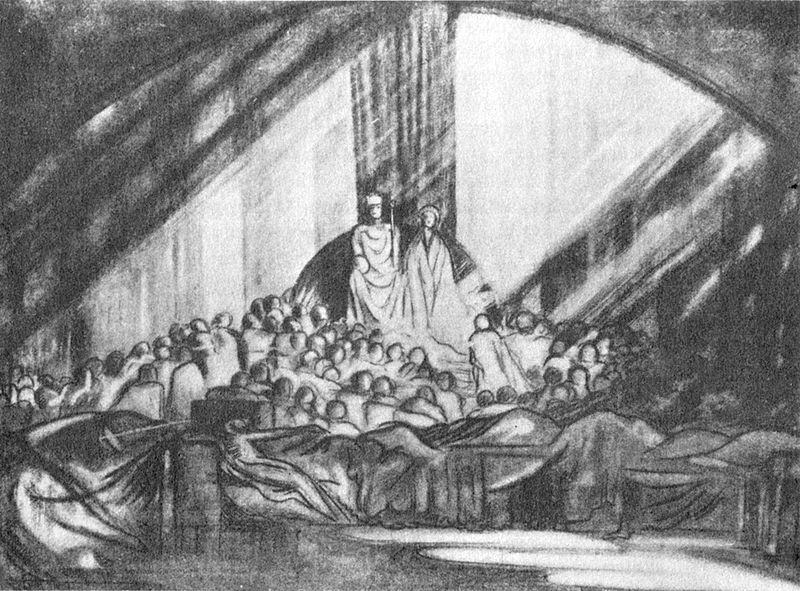

Edward Gordon Craig: stage design for Meyerhold's Hamlet at Moscow Arts Theatre 1908

Edward Gordon Craig: stage design for Meyerhold's Hamlet at Moscow Arts Theatre 1908

Hugo Ball + Emmy Hennings et al: Cabaret Voltaire, Zurich (1916)

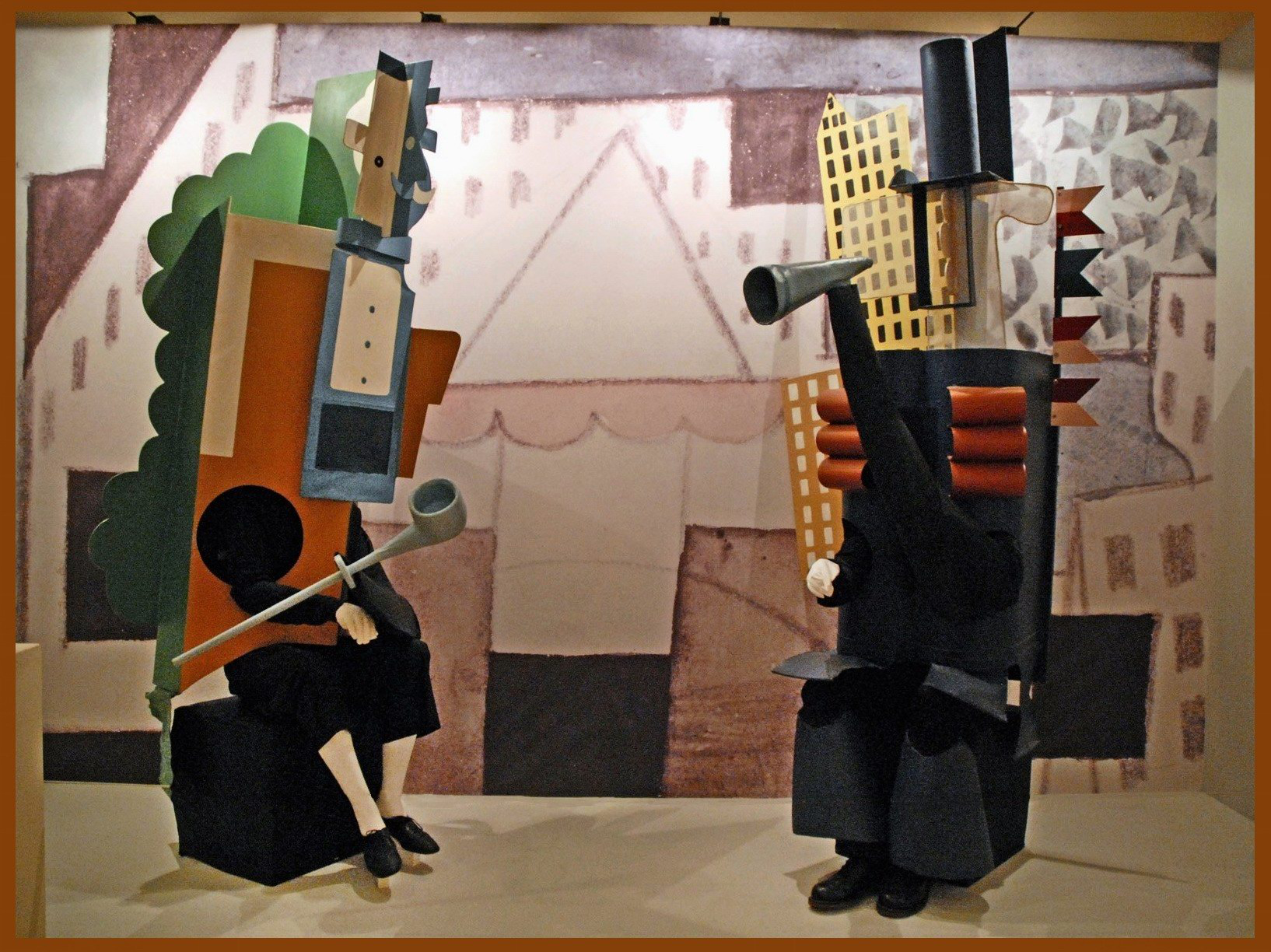

Diaghilev, Picasso et all: Parade (1917) stage-sets, costumes...

Oskar Schlemmer: Triadic Ballet costumes 1922

Oskar Schlemmer: Triadic Ballet costumes 1922

Anatol Petrytsky: Costumes for An Eccentric Dance 1922 (Encyclopedia of Ukraine)

Gustav Klutsis, Untitled (Screen Radio Orator No. 5), 1922

El Lissitzky: Pressa Exhibition in Cologne 1928

El Lissitzky: Pressa Exhibition 1928

El Lissitzky: Pressa Exhibition 1928

DADA: Berlin Dada installation 1920

Alexandr Rodchenko + Varvara Stepanova: Living Badge (Moscow Spartakiada parade 1923

Varvara Stepanova: Results of the First Five Year Plan 1932

Herbert Bayer: Extended Field of Vision c1928-1930

Herbert Bayer: Exhibition at Deutscher Werkbund, Paris 1930 Herbert Bayer: Expanded Field of Vision at Deutscher Werkbund, Paris 1930

Herbert Bayer: Expanded Field of Vision at Deutscher Werkbund, Paris 1930

Varvara Stepanova + Vsevolid Meyerhold: The Death of Tarelkin stage production 1922

There was this burst of revolutionary installation-stage - designs in the 1920s - in Berlin as the DADA movement blossomed in 1920s, many in the new Soviet Union celebrating the communist victory, then the story of Art and Techology migrates to the USA.

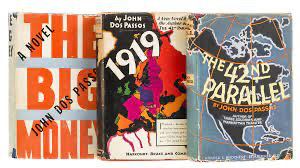

Dos Passos' stories of the 1919 - 1934 - presented in the three volumes of his USA books, broke new ground in a kind of panoptic, nation-wide story telling - mixing a helter-skelter of stream of consciousness in different forms, combining sketches of daily news, collages of impressions and potted biographies of some 'ordinary people' with the movers and shakers of the Twenties - the engineer-entrepreneurs like Henry Ford, Fred Taylor, with fictional running narratives on particular, iconic characters...

In the literary arts, it was John Dos Passos in his USA trilogy (1937) who for me introduced a wonderful mega-panoramic overview of what was happening in America post first world-war to early 1930s. His picture of the Twenties is a pan-optic poem of the triumph of technologies and new economic systems - and the people engineering these changes, and those reacting against them - emerging in this tumultuous period, which also featured writers of the calibre of Joyce, Fitzgerald, Woolfe, Hemingway, Lawrence, Pound, Eliot etc. Popular art like Elzie Segar's Popeye (1929)

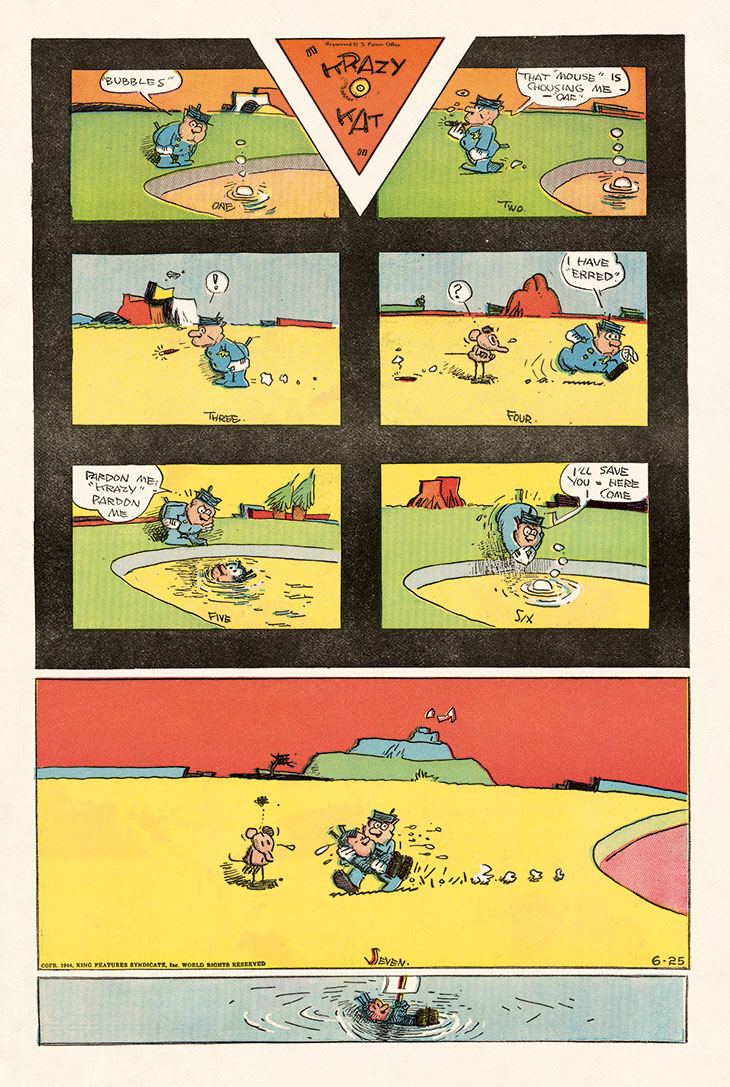

and George Herriman's genius Krazy Kat (1913-1944)

and George Herriman's genius Krazy Kat (1913-1944)

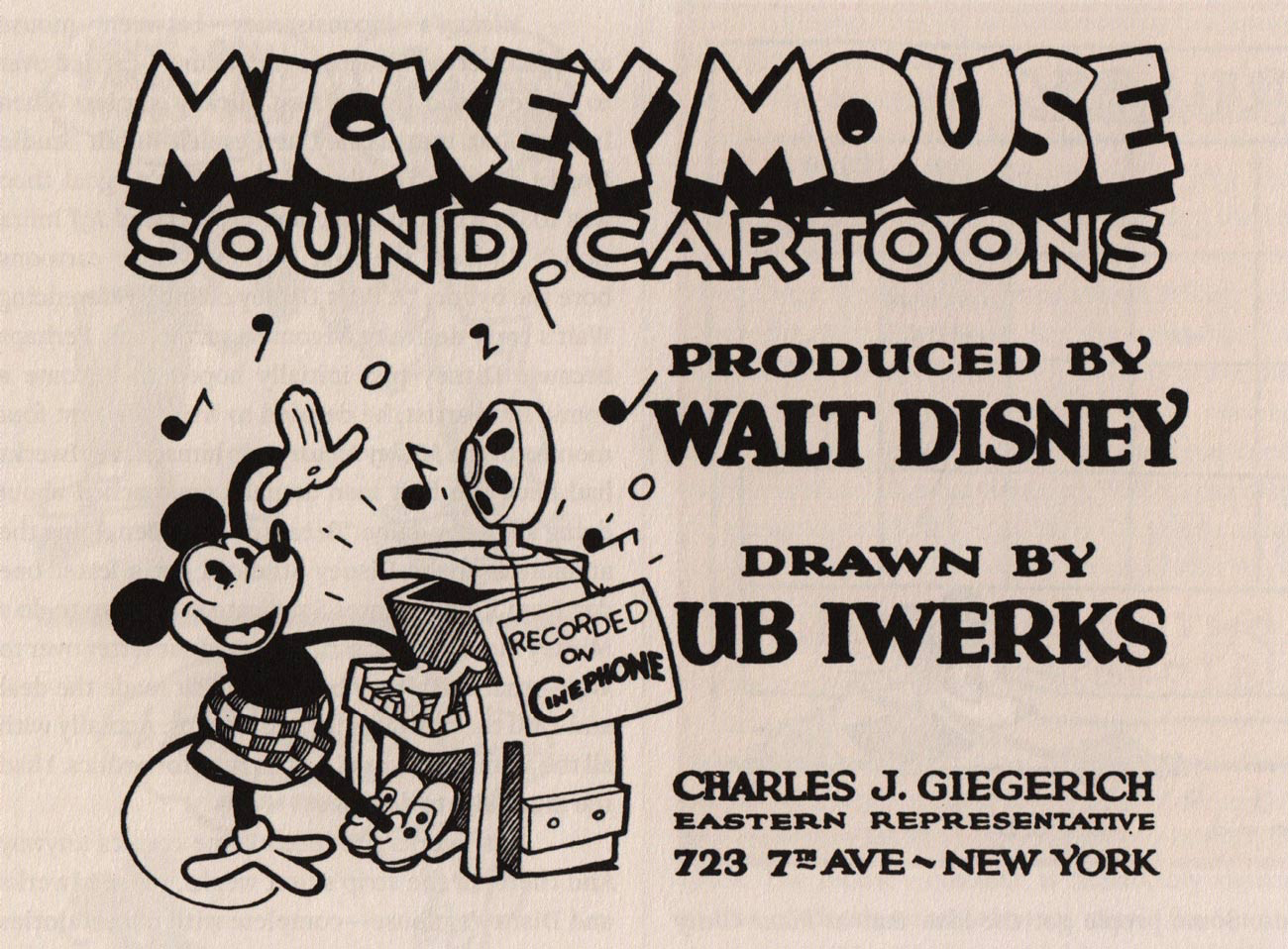

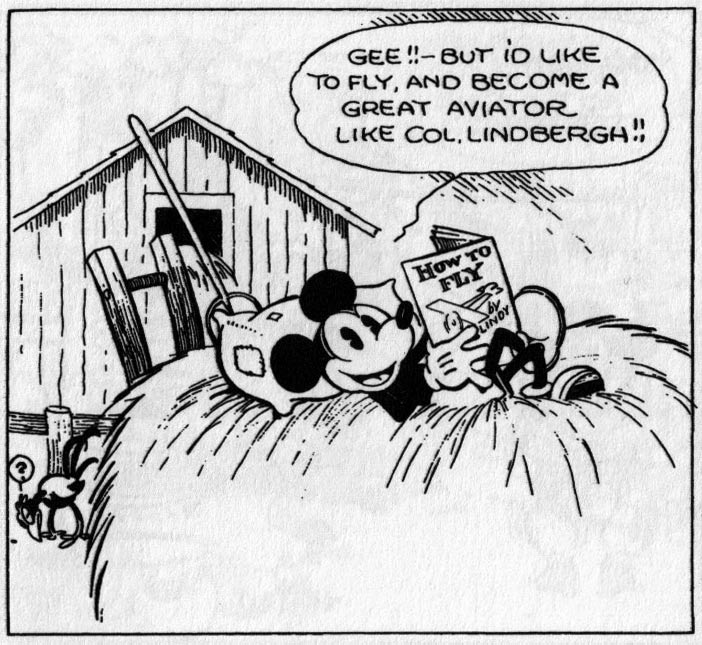

and Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney's invention of Mickey Mouse (1930):

Opening from 'Lost On A Desert Island' (13 January 1930), Mickey's first comic strip appearance. © Disney.

and Nat Grimswick and Dave Fleischer's Betty Boop (from 1930):

Burne Hogarth's strip of Rice Burroughs Tarzan (novel 1912 comic 1929):

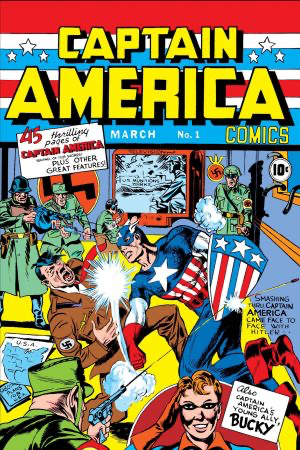

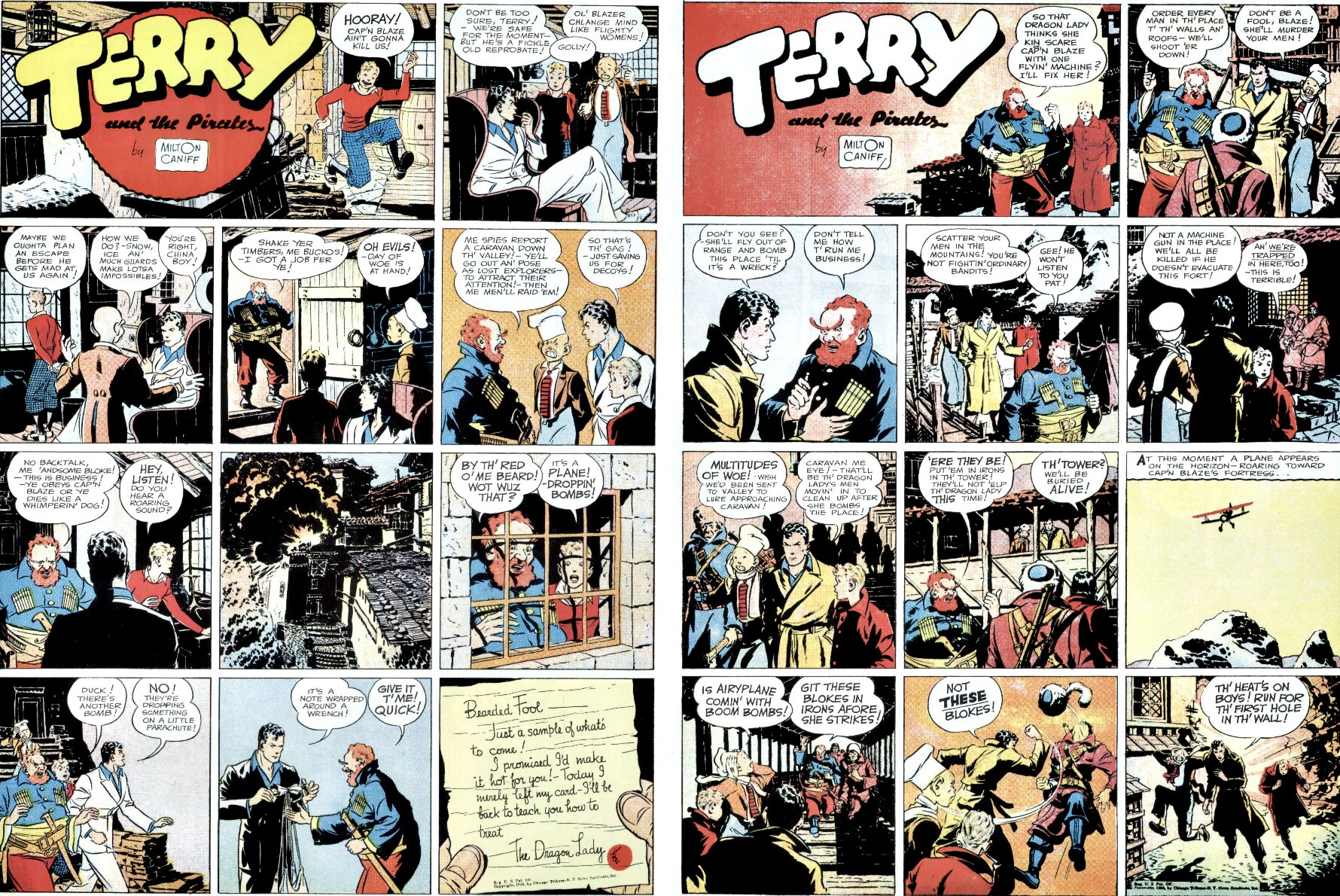

In the Sixties we learned to relish both the fine arts, and the popular arts - the Motown stuff, the Beatles and Stones stuff, the folk and folk-rock stuff we were listening to at the Ravel pub next to the Art College (fabulous 2/6 penny lunches and a great juke-box) - and I loved the illustrated narratives of the comics - you quickly discovered Jack Kirby of Marvel, and the classics Burne Hogarth, Milton Caniff (of Terry and the Pirates):

Jack Kirby: Captain America (from 1941)

Jack Kirby: Captain America (from 1941)

Milton Caniff: Terry and the Pirates (top:from 1934, bottom: 1943)

Milton Caniff: Terry and the Pirates (top:from 1934, bottom: 1943)

In the Sixties, I had bought some fabulous colour postcards of the 1939 New York World's Fair at a local jumble sale in Freshwater:

picture postcards of New York World's Fair 1939

Joseph Paxton: Crystal Palace at 1851 Great Exhibition, Kensington Gardens London

The visions elaborated in the World's Fairs - back to the original one: The sensational Crystal Palace at London Great Exhibition in 1851 - but especially the Paris World Expo in 1900, have always been ground-breaking - the Paxton Crystal Palace - the giant iron and glass pavilion in Kensington Gardens, the Eiffel Tower, dominating Paris, the simulated rides in 1900 (eg Lumiere's Photorama) - even the Skylon in 1950's Britain. But for an art student fascinated with audio-visuals, it was Expo67 in Montreal that was the stand-out game-changer - the Expo that caught the Zeitgeist full on.

Siegfried Giedion: Mechanisation Takes Command 1948

Siegfried Giedion: Mechanisation Takes Command 1948

I discovered this in the Library at Portsmouth College of Art c1965. It was the informed history of man-machine engineering that I'd been looking for. Giedion's book with its lavish black and white illustrations takes us through examples of design and engineering from early history to streamline and Hollywood Moderne -totally inspirational! (the digital media guru Lev Manovich traces more recent examples of engineering in his Software Takes Command of 2013 - essential reading!)

Josef Svboda: Diapolycran at Expo67 (see: my website: https://mediartinnovation.com/2014/05/24/josef-svoboda-diapolykran-the-creation-of-the-world-expo67/

Josef Svboda: Diapolycran at Expo67 (see: my website: https://mediartinnovation.com/2014/05/24/josef-svoboda-diapolykran-the-creation-of-the-world-expo67/

This is from media+art+innovation web archive c2015. I was a senior lecturer at Arts University Bournemouth at this time, and was trying to illustrate the Youngblood idea of 'expanded cinema'.

Gene Youngblood Expanded Cinema 1970 The first book that began to examine the 'multimedia' phenomena I was interested in.

What was the root of this fascination with multimedia 'light-shows'? I believe that its a continuing attempt to evoke that primordial immersive cultural experience that I've written about in the article: Ur Art - where it all came from by Bob Cotton 2021

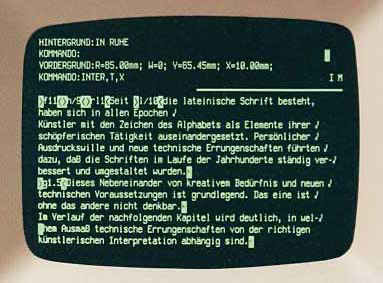

And there was the logic of the development of digital computing (from the late 1930s onwards) it seemed axiomatic that when Cage, Kaprow, Youngblood, Vanderbeek, Licklider and others had argued for the intermedia arts, this paralled the development of digital computing and I believed that these conjoining art-forms were artist's premonitions of the digital arts-spectrum to come in the following two or three decades (1970s-1990s). It was obvious by the late 1970s that soon the humble personal computer would be able to process typographics,

Input screen of a Linotype CRTronic c1982 - the embedded text and embedded typographic code - not dissimilar to hypertext markup language which was invented by Berners Lee in 1989. This was my first 'desktop publisher' - and it output to a 600dpi photo-printer! All this in the early 1980s!

graphic design, animations, sound-design, even video processing soon followed. Moore's Law (1965) even predicted the temporal window when we might see all this happening, and when it did, it came thick and fast, standardised by MPEG, we had CDs, CDROMs and a bit later CD-I from Phillips, and then DVD.

Al Hansen: A Primer of Happenings and Time/Space Art 1965

Avant-Garde and Counter-Culture artists like Vanderbeek, Paolozzi, Cage, Hansen,Ono, Higgins etc were 'tuned-in' to this multimedia zeitgeist as early as the late 1940s (at Black Mountain College, for example)

Allan Kaprow: Days Off - A Calendar of Happenings 1970 Hansen and Kaprow followed John Cage in developing this slightly scripted, place specific, performance art (1949-1970ish)

Hansen's book came out in time for me to add it to my reference list for my degree essay in 1967 on the Gesamptkunstwerk or Composite Work of Art. I also corresponded with Stan Vanderbeek, one of my counter-culture prophet-heroes, at this time and he kindly sent a stack of leaflets, poems, pamphlets, and a reading list of relevant books.And it was tough doing primary-source research material in that ancient pre-Web/Net universe...

Stan Vanderbeek: interior Movie-Drome 1964-65

Stan Vanderbeek: interior Movie-Drome 1964-65

A/V work then mostly consisted of 35mm slides, mixed with 16mm and 8mm colour film, and as video-tape became more widely available in the mid-late 1970s, the pointers towards convergent media were established in analogue forms.

Dick Higgins: Postface/Jefferson's Birthday 1964

First edition of International Times (IT) -"Founded by John 'Hoppy' Hopkins, Barry Miles, Jim Haynes, playwright Tom McGrath and others, International Times soon became the voice of the 1960s and early 1970s underground. It was was launched at London's Roundhouse on 14 October 1966 with a gig headlined by Pink Floyd" (The Guardian)

It was IT that was the very first newspaper for us of the 'underground', drawing upon the newly discovered coterie of young people who became visible to us all at the Poetry Incarnation in 1965.

These papers and books and others I found at Indica Books in Southampton Row. the founder Barry Miles describes it: "The shop had a large basement with a room off it where I had my office. In the back, accessible only from the entrance to the main building, were three more basement rooms, but they were very, very dark and difficult to access. We gave one to Alexander Trocchi for his Project Sigma, but he hardly ever used it. Similarly The Jeanetta Cochrane Theater, which was at the end of the street, rented another to house their script library, which was quite bulky, but we hardly ever saw them. In the main front basement, in October 1966, the International Times (IT) had its office, paying rent in the form of bundles of newspapers. They were there for a number of years, surviving a nasty police raid where every piece of paper including the phone books were seized, along with staff members’ address books and all the back issues. The raid was designed to put the paper out of business. The police kept everything for three months without bringing any charges – it was the corrupt Obscene Publications Squad we were dealing with – then they brought it all back in a lorry and threw everything down the stairs. People wonder why the hippies hated the ‘fuzz’; it’s because they were a bunch of fascist thugs who behaved as if they were in East Germany, knowing that the English middle classes would never believe for a minute that the police would do such things; ‘Evening all!’"

(http://barrymiles.co.uk/photo-library/indica-books-1965-1970/)

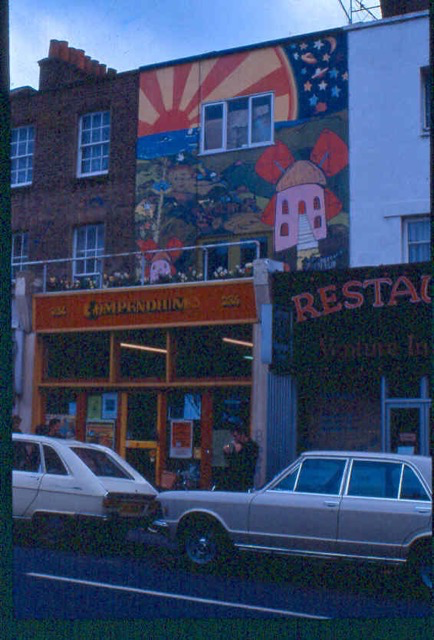

It was bookshops like Indica, Compendium and Better Books that saved our bacon in those days, 30 years before the Web/Net made research an online activity for most of us...

Compendium Books in Camden Town - just down the road from Camden Lock...

Compendium Books in Camden Town - just down the road from Camden Lock...

These shops, and Jim Haynes Drury Lane Arts Lab - and importantly for me, the First International Poetry Incarnation at the Albert Hall in 1965 (organised by Barbara Rubin, Barry Miles and Alan Ginsberg). This was a complete eye-opener and one of those revelatory moments - flowers being given away on the august steps of the Royal Albert Hall, me with beautiful Roz Parker, suddenly the underground revealed in blistering poetic actuality, Barbara Rubin whirling a Bolex movie-camera around her head, shooting film as fast as she could (only 78 frames/sec in those days) and centering herself and her camera immersively in the middle of the audience pits...

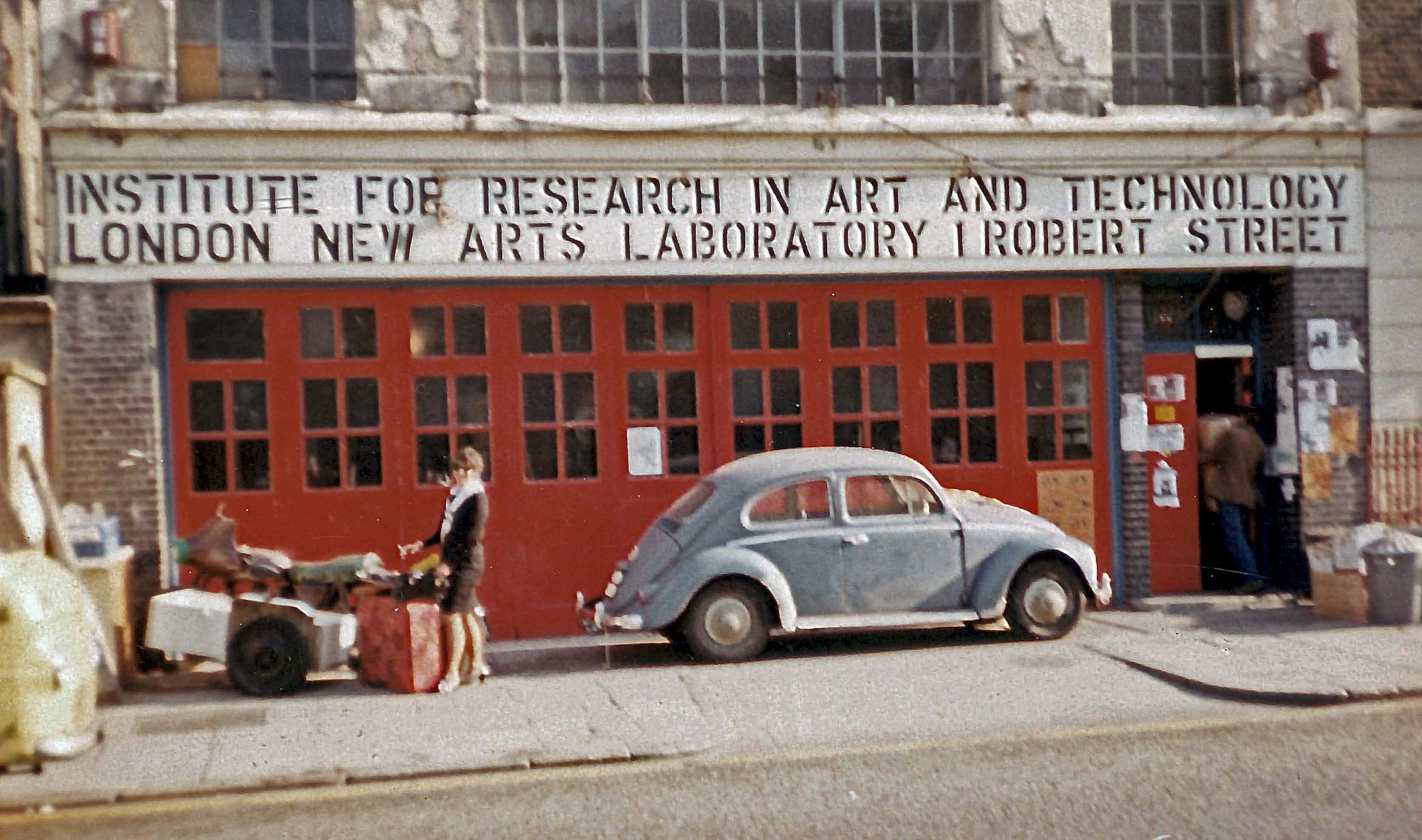

New London Arts Lab, Robert Street 1969

New London Arts Lab, Robert Street 1969

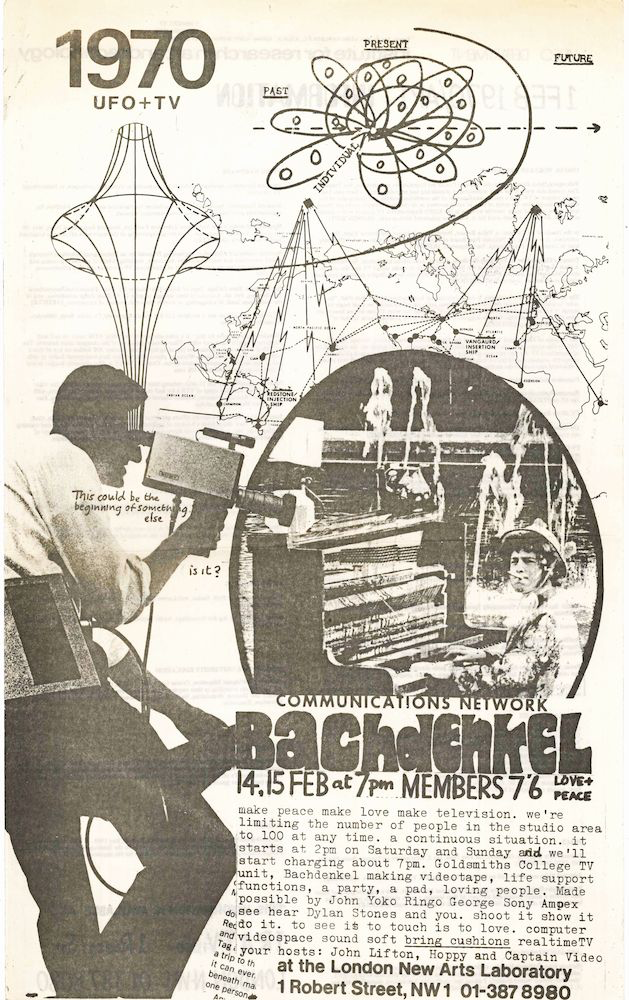

The convergence of Art and Technology in the late 1960s. spurred on by the Arts Labs emerging from the counter culture...notice the 'communications' network', Hoppy Hopkins, and 'videospace' - and the sponsors - 'John, Yoko, Ringo, George and Sony Ampex'...

"Following the closures of Better Books and Indica Bookshop, Compendium was for many years the main place for "the London literary avant-garde". It was a key venue for the British Poetry Revival and for availability of the texts of post-1968 political and cultural theory.[6] There was a large music section, with many imported US titles on blues, soul, jazz and rock and roll. Compendium also had sections for left-wing politics, philosophy, feminist books & the aforementioned 'mind, body, spirit' department, invariably referred to as 'the back desk'." (wikipedia)

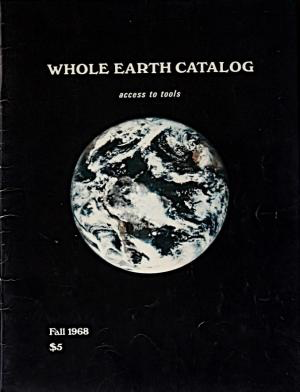

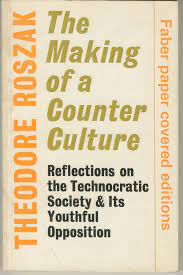

So, the media-map-profile of the underground (christened the Counter Culture by Theodore Roszak c1970) began to appear in the late 1960s, sped on its way by Stewart Brand's inspired Whole Earth Catalog in 1968

Stewart Brand: Whole Eath Catalog 1968

Stewart Brand: Whole Eath Catalog 1968

This breakthrough counter culture mail-order catalog invited its readers (and there were millions of us!) to send in product and service recommendations to feature in the catalog - it was our intellectual/practical social media in the late Sixties - a paper-equivalent 20 years ahead of the World Wide Web. It was a sourcebook for stuff - tools for the hand and the mind - and it was world-wide too...

Theodore Roszak The Making of a Counter Culture 1971

Fred Turner: From Counter Culture to Cyberculture 2006

Of course by the 1970s, we began to get do-it-yourself kit-hardware for building your own computers (MIT Altair 8800 kit in 1975). We had already enjoyed the computer-art exhibitions - Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA, curated by Jasia Reichardt in the UK,

and Jack Burnham's Software Exhibition at the Jewish Museum in NY:

and Jack Burnham's Software Exhibition at the Jewish Museum in NY:

and Information the first Data Art exhibition, curated by Kynaston McShine

Ursula Meyer: Conceptual Art 1972

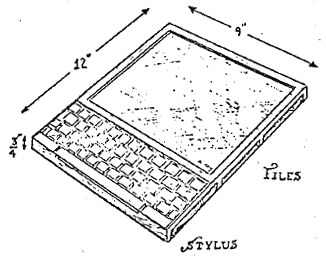

From Algorithm to Idea and back again - the intersection of cybernetics, computer art, software, information and conceptual art in the period 1967-1972 is remarkable, and it coincides with the breakthrough developments in software engineering of Douglas Engelbart, Ted Nelson and Alan Kay - Engelbart in his 1968 demonstration of what a personal computer might do - simulated by Engelbart on a mainframe computer, demonstrated by Ted Nelson and Andries van Dam in 1967 their hypertext editing system - again simulated on a mainframe computer... and also Alan Kay's concept of a Dynabook - begun in 1968 and published in 1972:

and in 1972, the largest LCD screen available was about 2" square. Here is Kay's sketch of 'the first really personal computer' - imagining a large touch-sensitive LCD screen and what we now know as an iPad, Tablet or Chrome-book - but with a lightweight, rubberised keypad, stylus for on-screen drawing, large LCD flat-screen - all visualised and conceptually integrated by Kay, along with an easy-to-learn programming language he invented called SmallTalk.

and in 1972, the largest LCD screen available was about 2" square. Here is Kay's sketch of 'the first really personal computer' - imagining a large touch-sensitive LCD screen and what we now know as an iPad, Tablet or Chrome-book - but with a lightweight, rubberised keypad, stylus for on-screen drawing, large LCD flat-screen - all visualised and conceptually integrated by Kay, along with an easy-to-learn programming language he invented called SmallTalk.

So by 1972, we had the conceptual homework outlined for the future development of personal computers, hypertext, and Kay's graphical-user-interface ideas - the focus for Apple Computer, and later Microsoft - and just about everyone else - and almost incidentally, we also had invented the basic hardware, software and network protocols for the ARPANet to transition to the Internet... A lot of this directly due to State financing and investment - a strategy analysed in 2013 by Marianna Mazzucato

Chomsky, Mazzucato, Zuboff, Klein, Schumacher, Loewenstein, Caroline Lucas, Yanis Varoufakis, and many others have realised that its greed and capitalism thats killing the planet, and have proposed tentative, alternative economic systems...