A history of Eco-Art and Eco-Media

The history of eco-art and eco-media really tabulates and records the history of our understanding and appreciation of our place in the world - our human understanding that we too are part of nature, and an intrinsic and increasingly threatening part of the planetary environment

"“Dissanayake argues that art was central to human evolutionary adaptation and that the aesthetic faculty is a basic psychological component of every human being. In her view, art is intimately linked to the origins of religious practices and to ceremonies of birth, death, transition, and transcendence. Drawing on her years in Sri Lanka, Nigeria, and Papua New Guinea, she gives examples of painting, song, dance, and drama as behaviors that enable participants to grasp and reinforce what is important to their cognitive world.”—Publishers Weekly:“Homo Aestheticus offers a wealth of original and critical thinking. It will inform and irritate specialist, student, and lay reader alike.”—American Anthropologist: A thoughtful, elegant, and provocative analysis of aesthetic behavior in the development of our species—one that acknowledges its roots in the work of prior thinkers while opening new vistas for those yet to come. If you’re reading just one book on art anthropology this year, make it hers.”—Anthropology and Humanism

"The Art Instinct combines two of the most fascinating and contentious disciplines, art and evolutionary science, in a provocative new work that will revolutionize the way art itself is perceived. Aesthetic taste, argues Denis Dutton, is an evolutionary trait, and is shaped by natural selection. It's not, as almost all contemporary art criticism and academic theory would have it, "socially constructed." The human appreciation for art is innate, and certain artistic values are universal across cultures, such as a preference for landscapes that, like the ancient savannah, feature water and distant trees. If people from Africa to Alaska prefer images that would have appealed to our hominid ancestors, what does that mean for the entire discipline of art history? Dutton argues, with forceful logic and hard evidence, that art criticism needs to be premised on an understanding of evolution, not on abstract "theory." Sure to provoke discussion in scientific circles and an uproar in the art world, The Art Instinct offers radical new insights into both the nature of art and the workings of the human mind."(Bloomsbury publications)

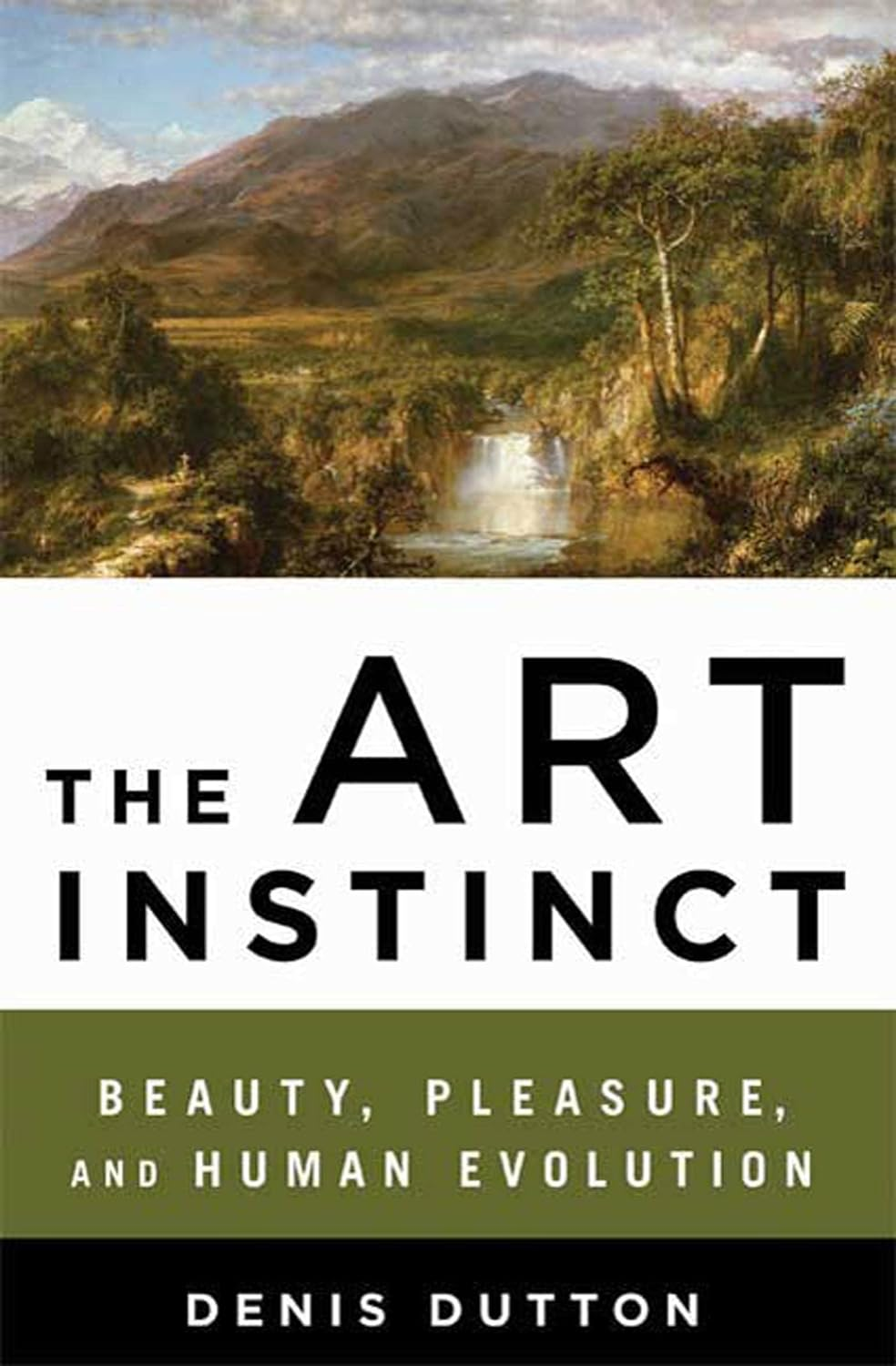

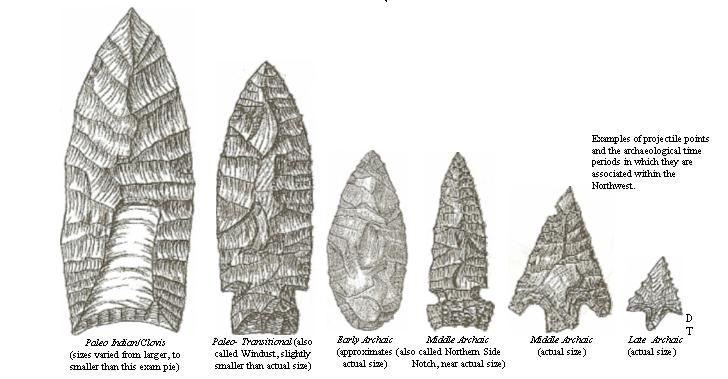

Dutton's argument is persuasive: Aesthetic creativity and appreciation is universal, albeit expressed in widely different ways around our world, and its expression has undoubtedly aided and guided our cultural evolution as a species - look at the refinement in the ergonomic knapping of arrow-heads - the appreciation of symmetry - as well as the intellectual understanding of their ergonomic effectiveness as hunting tools - the two go literally hand-in-hand. In every culture our aesthetic appreciation is married with practical usefulness, or is the result of our sense of crafting beauty in our hand-held Venuses and other portable art-objects of our primordial early nomadic cultures. The same with our evolution of talking, conversation, singing, rhyming, crafting clothing, body-decoration, masks - or the simple beauty of early ceramics.. Whatever we invented that was useful or satisfying to others is a product of observing, reasoning, experimenting and crafting - and cumulatively reflecting upon the things we have created and used...

flint-knapping evolution in Puget Sound (http://www.pugetsoundknappers.com/)

flint-knapping evolution in Puget Sound (http://www.pugetsoundknappers.com/)

From earliest to most recent ancient times - the sense of beauty and quest for symmetry become the dominant theme, married to the desire to improve efficiency (introducing tangs and reducing size). But I'm rather focusing on the modern age - from the mid-19th century until now - in this illustrated article - really from Darwin and Wallace onwards...but first, just some of the early mythography of Nature:

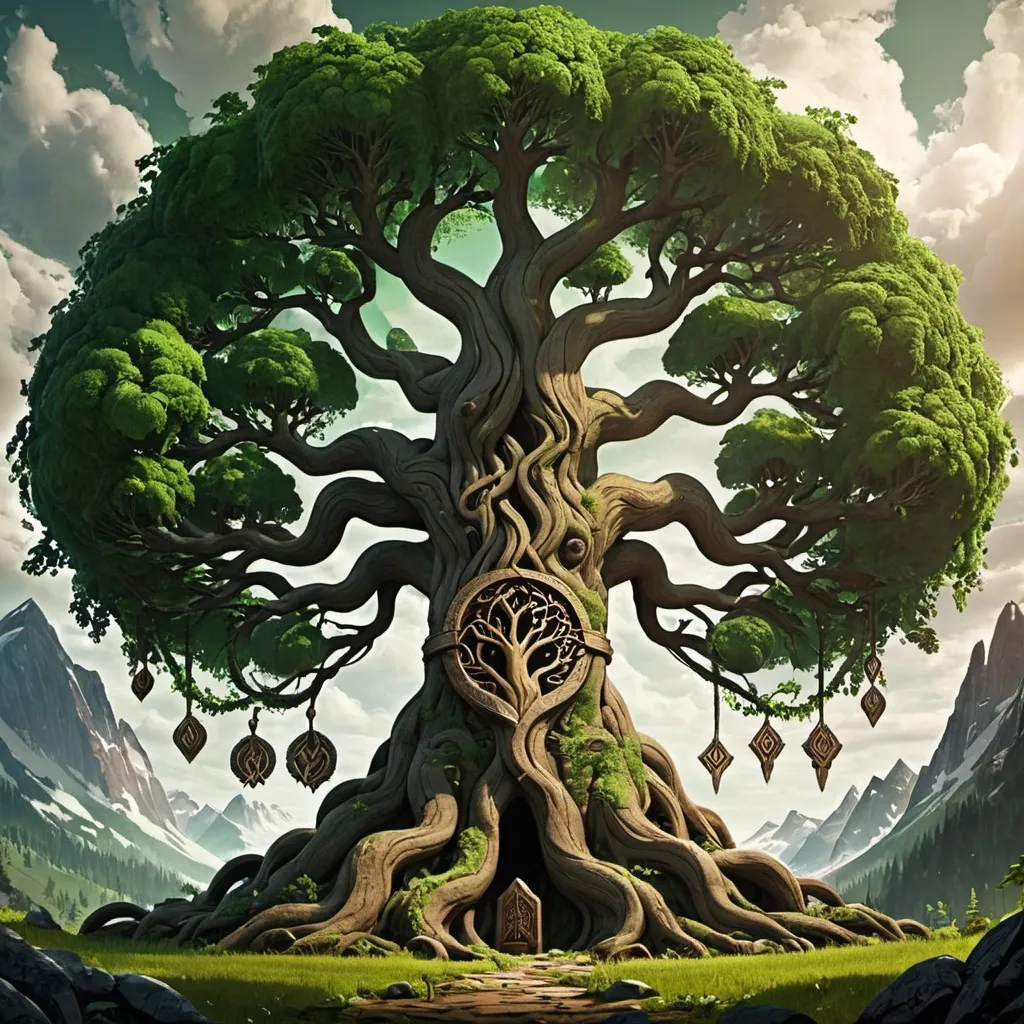

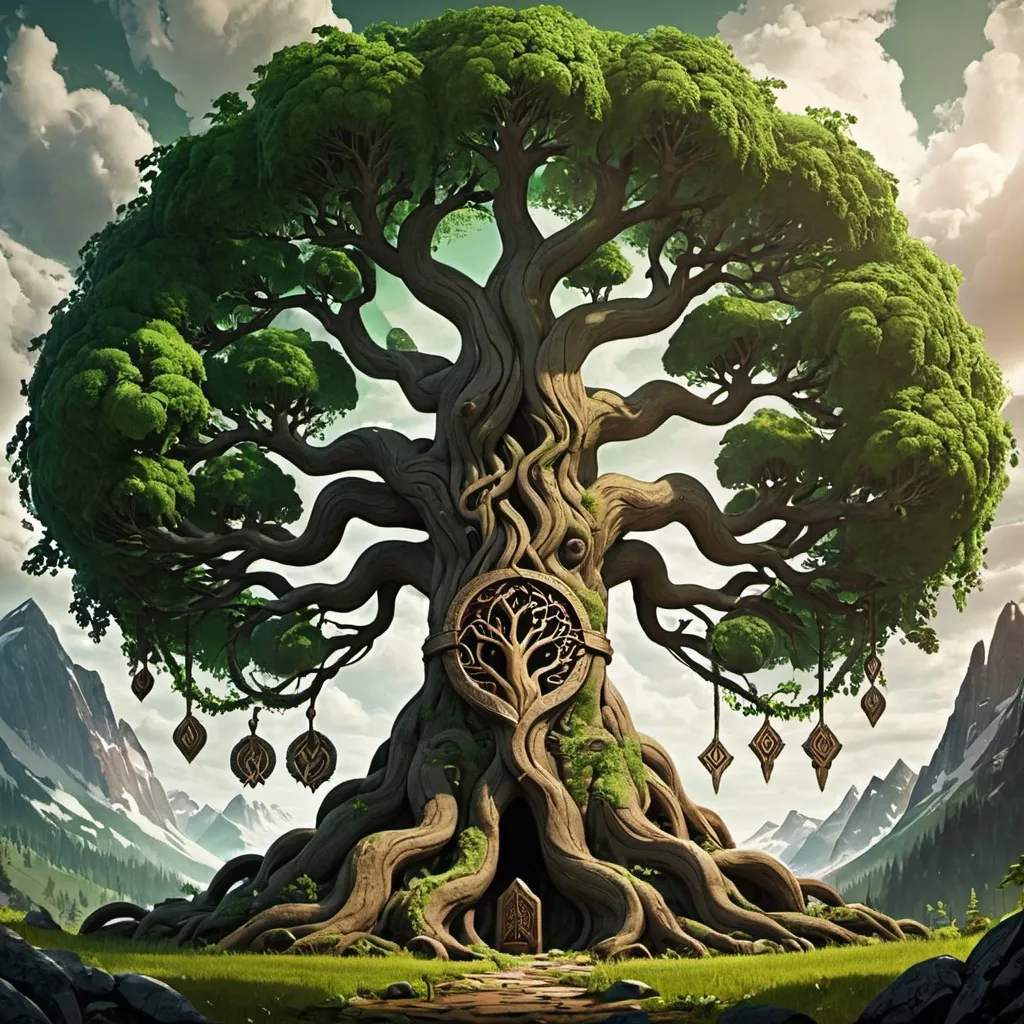

(prompt) Yggdrasil tree, nordic mythology theme, enormous, gigantic, lively, naturally, a little mystery (openart SDXL)

(prompt) Yggdrasil tree, nordic mythology theme, enormous, gigantic, lively, naturally, a little mystery (openart SDXL)

What the AI chatbot has generated here is the result of trolling the Large Language Model - a collection and collation of mostly public-domain information (text, pictures, movies, data, fact and fiction etc) for mentions of Yggdrasil which it combines with pictorial information about Norse and Celtic art and symbolism, tree symbolism, and combining these 'cleverly' into a picture set in a mountain-range - pretty good, I'd say.

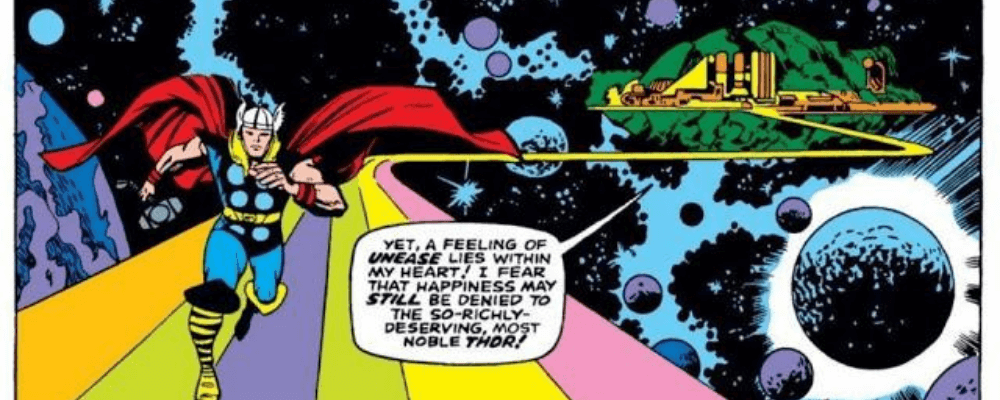

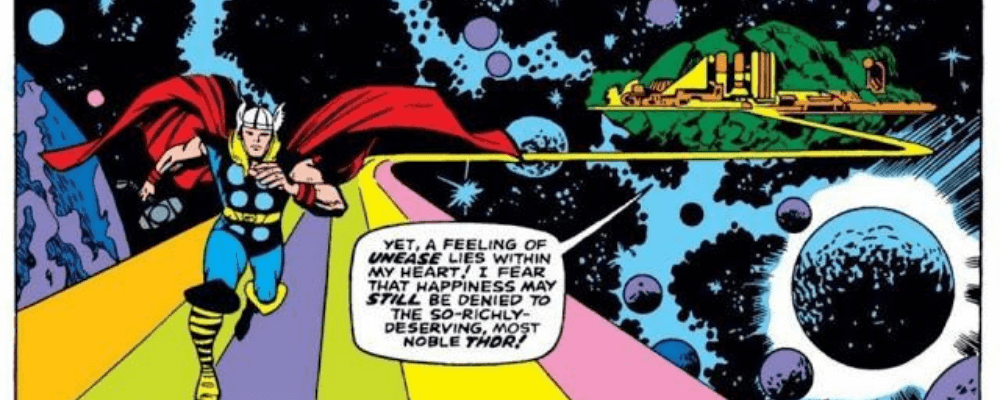

Jack Kirby and Stan Lee: Marvel Comics Thor 1962 (first appearance) 1966(solo comic) Thor on Bifrost - the Rainbow Bridge - the wonder and joy of the rainbow - even way before we knew about Newton and wavelengths of the visible light spectrum - and its delightful curve - inspired primordial responses in myth, symbolism and religion - Jack Kirby's cinematic drawings for Marvel.

Jack Kirby and Stan Lee: Marvel Comics Thor 1962 (first appearance) 1966(solo comic) Thor on Bifrost - the Rainbow Bridge - the wonder and joy of the rainbow - even way before we knew about Newton and wavelengths of the visible light spectrum - and its delightful curve - inspired primordial responses in myth, symbolism and religion - Jack Kirby's cinematic drawings for Marvel.

I was a great fan of Marvel Comics in the Sixties and enjoyed Stan Lee's plotting and Larry Lieber's writing, and of course the heavily cinematic lensing of Jack Kirby's faultless drawing.

James Audobon: The Carolina Parrot from Audobon: The Birds of America 1827-1839

James Audobon: The Carolina Parrot from Audobon: The Birds of America 1827-1839

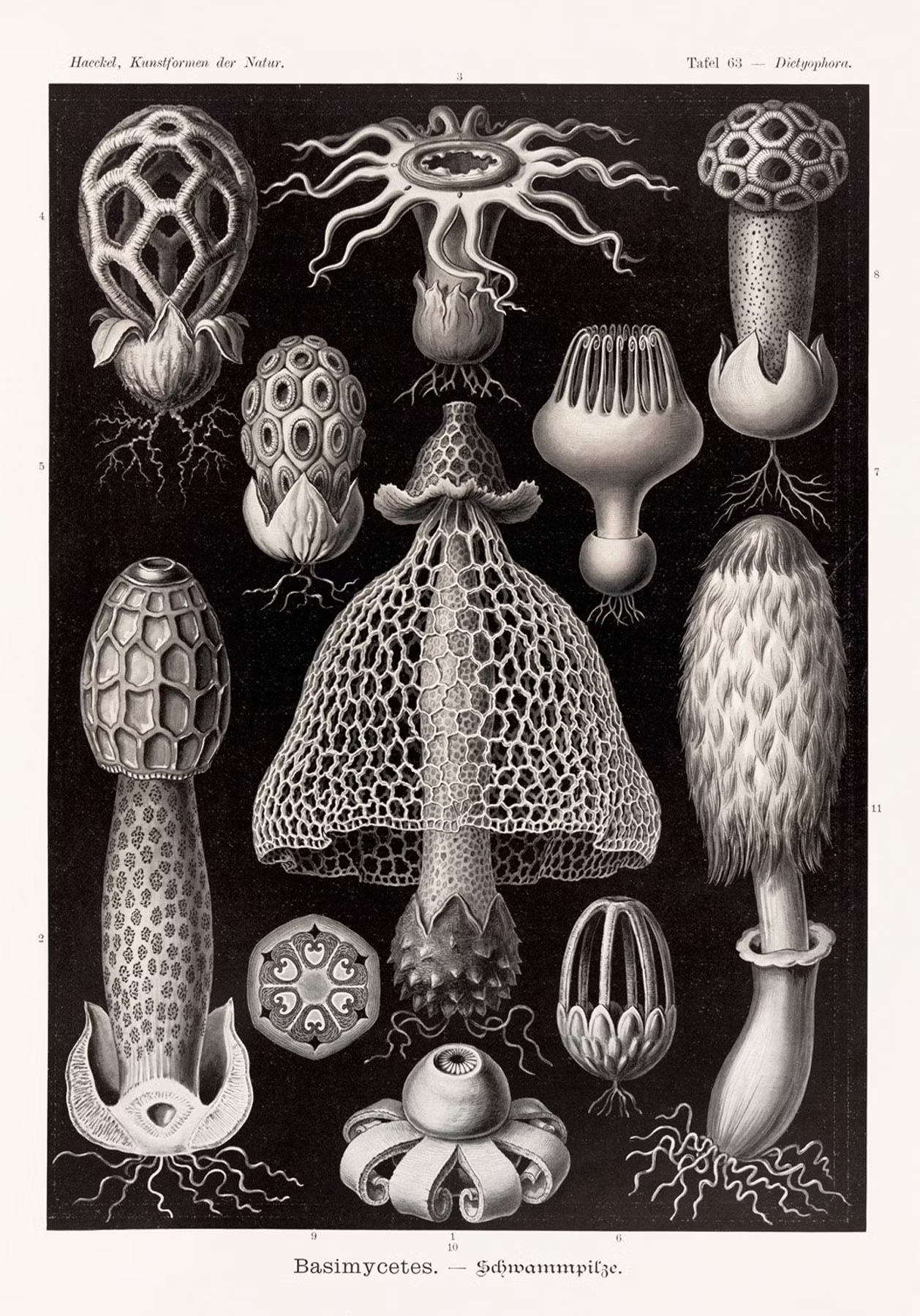

We owe a lot to the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel: It was the discovery of his Kunstformen der Natur (1904) that kick-started my own interest in eco-art - and in eco-media too - as it was Haeckel's idea to have his beautiful watercolours and drawings reproduced in litho prints - made by the lithographer Adolf Glitsch - effectively making his work available to a much wider audience/marketplace - and this from the man most responsible for putting Darwin's thesis before the German public...

"The term ‘ecology’ was coined by the German scientist and theorist Ernst Haeckel in 1866. ‘By ecology, we mean the whole science of the relations of the organism to the environment including, in the broad sense, all the “conditions of existence.”’ (Ernst Haeckel, Generelle Morphologie 2: 286; translation from Stauffer 1957, p. 140.) The creation of the term ‘ecology’ clearly did not mark an epoch in the history of science; Darwin and some of his correspondents complained mildly about Haeckel’s propensity for making up words, but did not quarrel about the sense behind his definitions. ‘The number of new words … is something dreadful’, Darwin wrote to T. H. Huxley on 22 December 1866. ‘He seems to have a passion for defining, I daresay very well, & for coining new words.’ "

"Ecology is the study of all those complex interrelations referred to by Darwin as the conditions of the struggle for existence" (Inaugural lecture 1869; translation by W. C. Allee quoted in Stauffer 1957, p. 141).

It was Haeckel's definition and naming of 'ecology' - resting upon Darwin's Origin of Species (1859) and Darwin's collaboration with Alfred Russell Wallace. My own history of this topic stemmed from reading The Worm Forgives the Plough by the 'poet of ecologists', John Stewart Collis, when I was about 25 (1970 ish)

Collis' book is set in World War 2 when he was working in East Anglia as part of the Land Army, and this period was before the modernisation and mass-mechanisation of agriculture in the 1950s and 1960s - the plough and wagons were still drawn by shire horses, and most of our Land was naturally organic and free of chemicals. His writing is poetic - for example, describing the beauty of the water cycle from rain to ground-water then the 'trees as giant fountains' pumping water into the air again. Worms of course, played an incredibly important part in aerating and fertilising the soil. In my own reading history this is related to Ronald Blythe's wonderful Akenfield - Portrait of an English Village, though this was published in 1969. It is a description of a village in Suffolk through recent time:

Collis' book is set in World War 2 when he was working in East Anglia as part of the Land Army, and this period was before the modernisation and mass-mechanisation of agriculture in the 1950s and 1960s - the plough and wagons were still drawn by shire horses, and most of our Land was naturally organic and free of chemicals. His writing is poetic - for example, describing the beauty of the water cycle from rain to ground-water then the 'trees as giant fountains' pumping water into the air again. Worms of course, played an incredibly important part in aerating and fertilising the soil. In my own reading history this is related to Ronald Blythe's wonderful Akenfield - Portrait of an English Village, though this was published in 1969. It is a description of a village in Suffolk through recent time:

"Ronald Blythe's perceptive and vivid evocation of the rural Suffolk he had known since childhood was acclaimed as an instant classic when it was published in 1969. It reverberates with the voices of the village inhabitants, from the reminiscences of survivors of the Great War evoking days gone by, to the concerns of a younger generation of farm-workers and the fascinating and personal recollections of, among others, the local schoolteacher, doctor, blacksmith, saddler, district nurse and magistrate. Providing insights into the land, education, welfare, class, religion and death, Akenfield forms a unique document of a way of life that has, in many ways, disappeared." (Penguin Books description)

And see also Francis Brett Young's Portrait of a Village (1937) which covers the same late 19th to early 20th century period - a period when we were ingesting Darwin and realising the import of Wallace and Haeckel's ecosystems.

BTW, I have vivid memories of being sent by my mum (c1955) to collect a jugful of fresh milk - still cool - from the horse-drawn cart with the big aluminium churns, that came from the farm in Colwell Lane, less than half a mile away from our house in Silcombe Lane...

Marianne North: A Darjeeling Oak festooned with a Climber 1878. North was a prolific explorer and wildlife painter - her meticulous paintings tended to illustrate not just a specific plant (growing in isolation), but importantly she sought to show the environment (the ecosystem) which the plant inhabited. There's a collection of her work at Kew Gardens West London, donated by her in a special gallery...

Marianne North: A Darjeeling Oak festooned with a Climber 1878. North was a prolific explorer and wildlife painter - her meticulous paintings tended to illustrate not just a specific plant (growing in isolation), but importantly she sought to show the environment (the ecosystem) which the plant inhabited. There's a collection of her work at Kew Gardens West London, donated by her in a special gallery...

Marianne North: Wild Flowers of Ceres South Africa 1882

Marianne North Gallery Kew Gardens (North gallery)

Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac 1949

Aldo Leopold: A Sand County Almanac 1949

"First published in 1949 and praised in The New York Times Book Review as "a trenchant book, full of vigor and bite," A Sand County Almanac combines some of the finest nature writing since Thoreau with an outspoken and highly ethical regard for America's relationship to the land.Written with an unparalleled understanding of the ways of nature, the book includes a section on the monthly changes of the Wisconsin countryside;

another part that gathers informal pieces written by Leopold over a forty-year period as he travelled through the woodlands of Wisconsin, Iowa, Arizona, Sonora, Oregon, Manitoba, and elsewhere; and a final section in which Leopold addresses the philosophical issues involved in wildlife conservation. As the forerunner of such important books as Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, Edward Abbey's Desert Solitaire, and Robert Finch's The Primal Place, this classic work remains as relevant today as it was forty years ago."

(Abebooks decription)

Just the title of this landmark book, together with the reputation of Leopold, - and his son Lumo's selection of the profuse line drawings that illustrate the book, make this as signficant as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring of a decade or so later.

I've always been fascinated by ideas of how we might live outside (or beyond) the ghastly capitalist system we now inhabit - stemming from ideas of communalism and socialism in early Christianity, for example:

"All who believed were together and had all things in common; they would sell their possessions and goods and distribute the proceeds to all, as any had need. ... Now the whole group of those who believed were of one heart and soul, and no one claimed private ownership of any possessions, but everything they owned was held in common. ... There was not a needy person among them, for as many as owned lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold. They laid it at the apostles' feet, and it was distributed to each as any had need."( Acts 2:44–45, Acts 4:32–35)

This (the transition of tribal communalism and mutual aid to the origins of capitalism) is important in a summary history of eco-art and media, as capitalism (consumer capitalism) is now recognised by many as being the root cause of climate-change: over-production, over-consumption, pillaging of natural resources, lax global corporate governance, etc etc, has been criminally negligent and self-serving in matters of carbon-fuelled over-consumption, pillaging of natural resources (that after all, are the heritage of everyone), stealing nature's 'designs' by patent-law on genes and genetic therapies, privatising water (et cetera)...

Petr Kropotkin: Mutual Aid - A Factor of Evolution 1902

"Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution is a 1902 essay collection by Russian anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin. The essays, initially published in the English periodical The Nineteenth Century between 1890 and 1896, explore the role of mutually-beneficial cooperation and reciprocity (or "mutual aid") in the animal kingdom and human societies both past and present. It is an argument against the competition-centred theories of so-called social Darwinism, as well as the romantic depictions of cooperation presented by writers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued it was motivated by universal love rather than self-interest. Mutual Aid is considered a fundamental text in anarchist communism, presenting a scientific basis for communism alternative to the historical materialism of the Marxists. Many biologists also consider it an important catalyst in the scientific study of cooperation." (Amazon books summary)

I'm intellectually and emotionally attracted to 'mutually beneficial cooperation' and the importance of altruism in our world society, as opposed to the base attractions of capitalism - competition, greed and private ownership. I'm also drawn to the philosophical anarchism of William Godwin, Mikhail Bakunin, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman - these last two were closely involved with the anarchist-leaning magazine Mother Earth - and together these form the philosophical roots of Eco-Anarchism or Green-Anarchism

'Green Anarchy' or Eco-Anarchism flag/logo.

Deriving ultimately from the 19th century philosophies espoused by William Godwin, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, and the anarchist communalism of Mikhail Bakunin as he argued against the Marxist ideas of the Bolshevik faction, eco-Anarchism or Green Anarchism has multiple influences and multiple directions of evolution from Greening Everything back to a kind of low-growth medieval cooperative community to anti-globalist, animal rights and anti-capitalist, and feminist syndicalisms... the most informative source I found was the setailed, wide-ranging essay by Matthew Hall: Beyond the Human: Extending Ecological Anarchism in Environmental Politics Vol 20 issue 3:

"Environmental philosophers assert that hierarchical orderings of the natural world have played a major role in the ongoing human project of dominating nature (Warren 2000, Plumwood 2002, Hall 2011). Philosophical hierarchies of the natural world are often anthropocentric, with humans regarded as superior on the basis of possessing ‘uniquely human’ characteristics. Non-humans are situated below humans because they ‘lack’ such attributes. An example from antiquity is the ‘great chain of being’. Reasoning humans are at the top of the chain, followed by animals incapable of reasoning, and insentient plants (Hall 2011). It is a feature of such hierarchies, that they are associated with claims that non-human are purely resources for humans. Lower in the hierarchy of mind and presence, plants and animals are presumed to have no purpose of their own and so their existence is entirely subverted to human ends. This enforces the binary dualism of humans/nature – one existing solely as an instrument for the other (Plumwood 2002). It is also a feature of such hierarchies that human ‘superiority’ is based upon a partisan assessment made by human beings (Taylor 1981). Humans are only superior because they deem themselves to be so.

Anarchists reject imposed authority, hierarchy and domination and seek to ‘establish a decentralised and self-regulating society consisting of a federation of voluntary associations of free and equal individuals’ (Marshall 2008, p. 3). Anarchism is therefore a promising political philosophy for undermining the human hierarchy and domination of the natural world and exploring the exclusion and subjugation of the non-human." (Matthew Hall op cit)

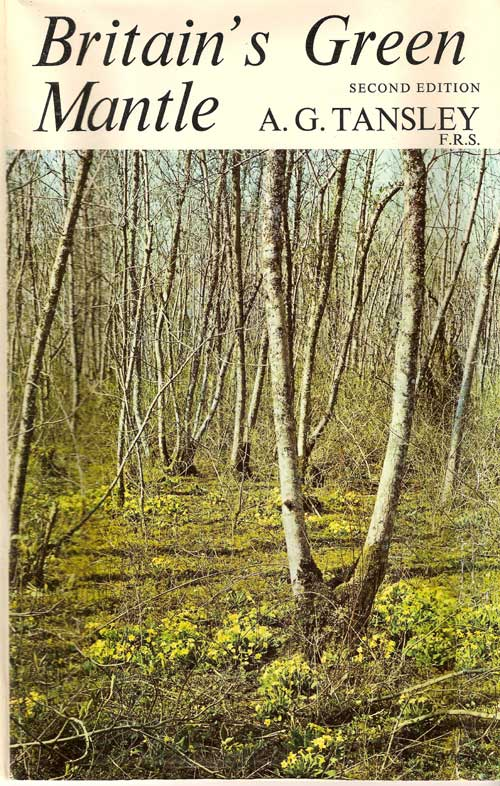

Arthur Tansley: British Ecological Society 1913 Arthur Tansley: The British Ecological Society - kick-started by Tansley's The Problems of Ecology (1904) was founded in 1913 - the first such society in the whole World! And the next half-century featured a gamut of important environmentalist news: Eve Balfour's Soil Association founded in 1946, grew out of practical experiments she had conducted comparing chemical and organic farming methods, summarised in her (1943)

Arthur Tansley: The British Ecological Society - kick-started by Tansley's The Problems of Ecology (1904) was founded in 1913 - the first such society in the whole World! And the next half-century featured a gamut of important environmentalist news: Eve Balfour's Soil Association founded in 1946, grew out of practical experiments she had conducted comparing chemical and organic farming methods, summarised in her (1943)

The Living Soil...

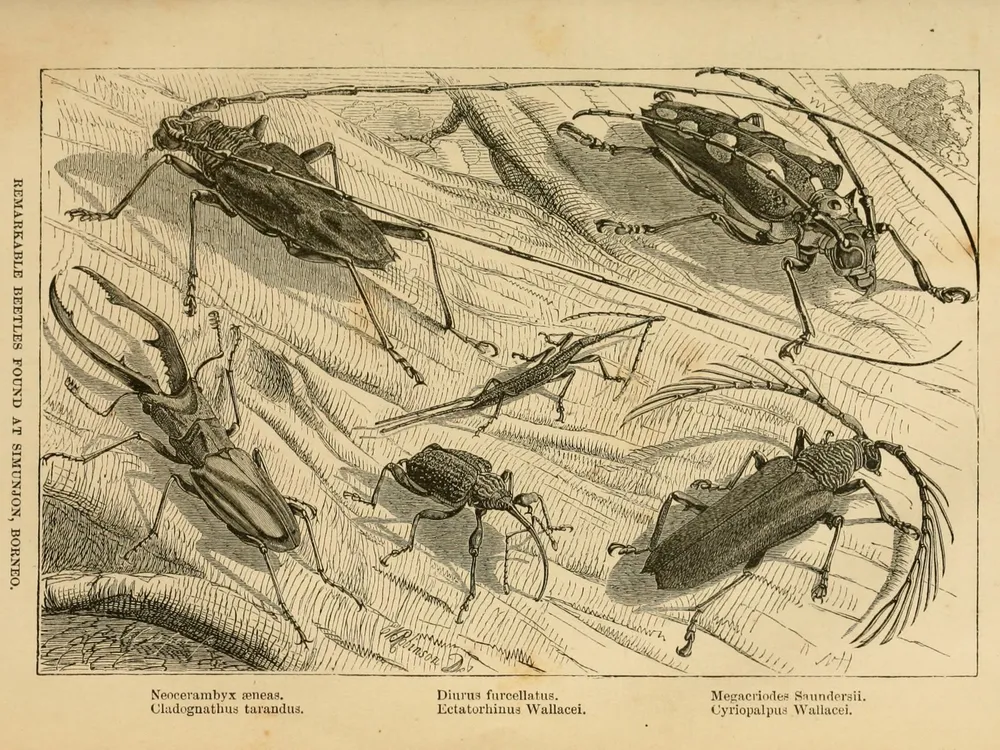

Alfred Russell Wallace: schematic drawing of related beetles from Borneo.

Alfred Russell Wallace: schematic drawing of related beetles from Borneo.

Wallace was one of the first scientists to warn of the dangers of deforestation, monoculture and soil-erosion, in his Tropical Nature & Other Essays 1878), so this early history of eco-art and media focuses on three men: Wallace, Darwin and Haeckel.

Wallace: On the Law which has regulated the Introduction of New Species" (1855)

Ernst Haeckel: from Kunstformen der Natur

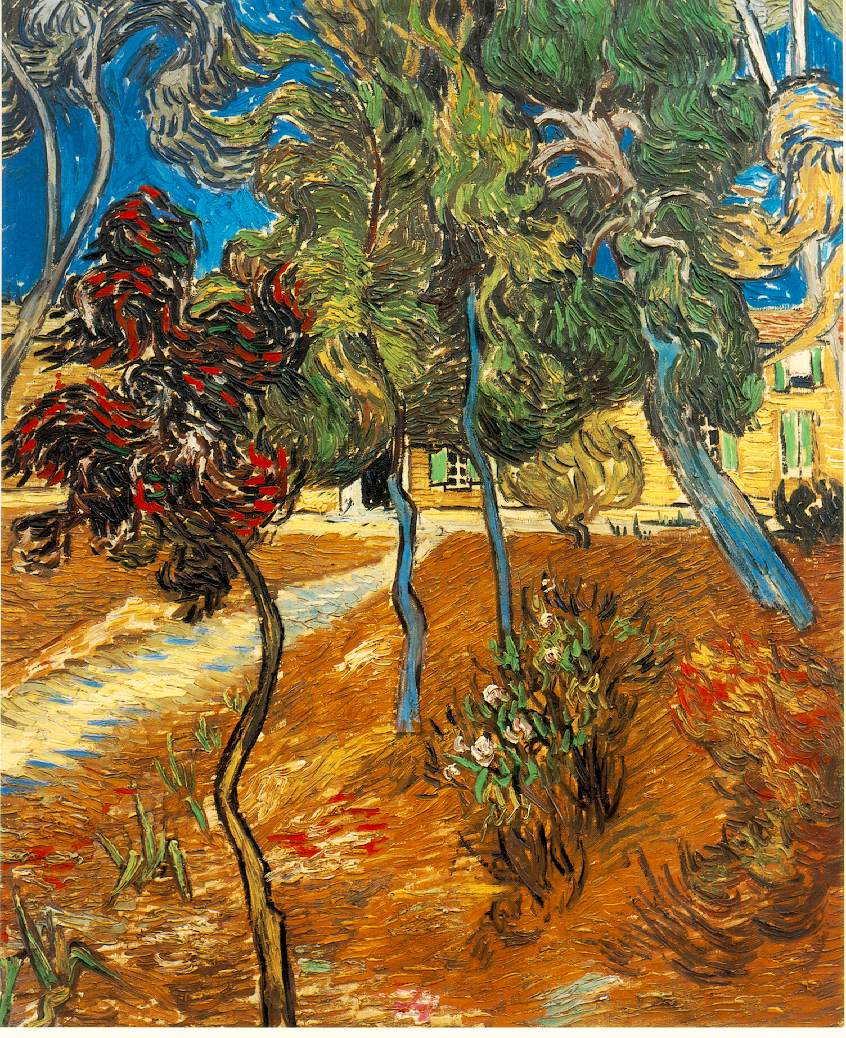

Haeckel's are remarkable drawings and paintings - transcending simple graphic recordings as much as an ornithological print by John James Audubon transcends simple descriptive drawings of birds. Haeckel's plates in Kunstformen der Natur are exceptional - and hint at the richness of the ecosystems he is exploring and discovering

Charles Darwin: Origin of Species 1859

Ernst Haeckel:

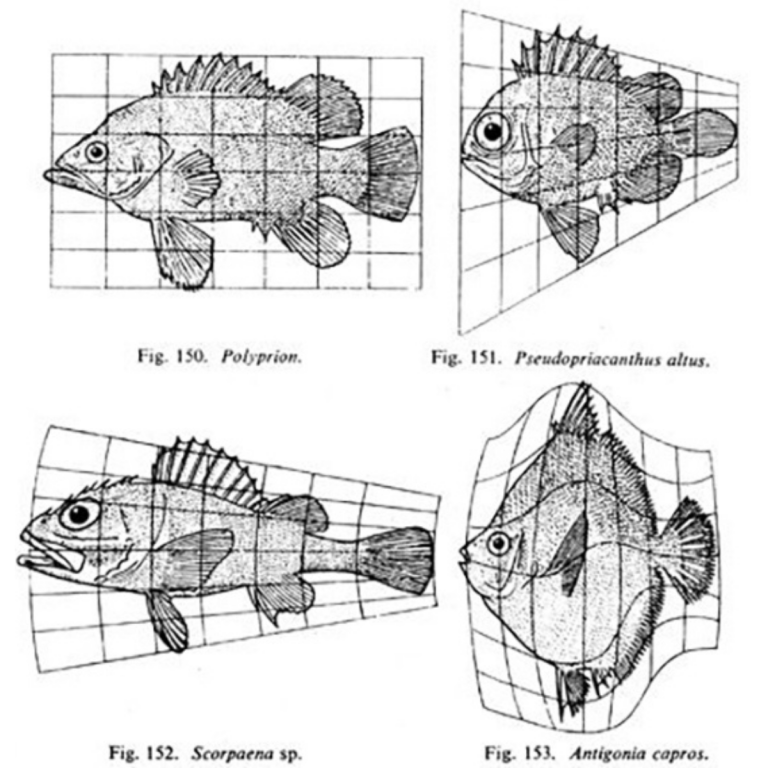

D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson: On Growth and Form(1917). The art of Wentworth Thompson focused upon the physical mechanics of how things grow in Nature and on their capacity for self-organisation

D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson: plate from On Growth and Form

D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson: plate from On Growth and Form

Alexander Bogdanov: Tektology (The General Science of Organisation) 1913

"Tektology is a universal natural science. It is just being conceived; but since the entire organizational experience of mankind belongs to it, its development should be swift and revolutionary, as it is revolutionary in its nature." (Bogdanov)

This little-known work was the foundation of systems science, the core theory that later gave birth to Tansley's Ecosystem theory, to Weiner's cybernetics and Ludwig von Bertllanfy's General Systems Theory - and played a role too in the birth of Bolshevist Communism in Russia.

"The Constructivists wholeheartedly endorsed the future of Soviet socialism and they took a leading role in shaping proletarian ideology. Drawing on Bogdanov’s theories of tektology and proletarian art, the Constructivists synthesized their artistic vision with the proletarian cultural movement. The Constructivists ’ desire to organize the collective as “worker-organisers” through “production” art was indebted to Bogdanov. In this regard, Constructivist work during the laboratory phase is paramount for understanding the role that Bogdanov’s tektology played in the development of Constructivist theory. In 1929, Dziga Vertov produced Man with a Movie Camera , and an analysis of tektological methods used in this film reveal Vertov’s ideologic al motivations. It is on this basis – building ideology – that tektology furnished a viable solution to the Constructivist pursuit of uniting the theoretical and the practical in their art." (Melody A. MacKenzie 2008)

The chain of reasoning sparked by Bogdanov's Tektology - his theory of systems - included further exploration of Tansley's ecosystems, Norbert Weiner's work on cybernetics (1948),

The chain of reasoning sparked by Bogdanov's Tektology - his theory of systems - included further exploration of Tansley's ecosystems, Norbert Weiner's work on cybernetics (1948),

Howard and Eugene Odum: The Fundamentals of Ecology 1953

Howard and Eugene Odum: The Fundamentals of Ecology 1953

"The late Eugene Odum was a pioneer in systems ecology and is credited with bringing ecosystems into the mainstream public consciousness as well as into introductory college instruction. FUNDAMENTALS OF ECOLOGY was first published in 1953 and was the vehicle Odum used to educate a wide audience about ecological science. This Fifth Edition of FUNDAMENTALS OF ECOLOGY is co-authored by Odum's protege Gary Barrett and represents the last academic text Odum produced. The text retains its classic holistic approach to ecosystem science, but incorporates and integrates an evolutionary approach as well. In keeping with a greater temporal/spatial approach to ecology, new chapters in landscape ecology, regional ecology, and global ecology have been added building on the levels-of-organization hierarchy..."

By the early 1950s - as Odum demonstrated, the basics of ecology, as far as scientists were concerned, were fairly well mapped out, and by 1957 his mentor, the English George Evelyn Hutchinson had published on his favoured topic - limnology - the eco-science of inland waters and marshlands in A Treatise on Limnology.

Hutchinson also compiled the first bibliography of the work of Rachel Carson - the person who was to brilliantly popularise the whole field of ecology, and the threats and dangers we humans were posing to our environment by our over-use of DDT and other pesticides threatening and killing wild birds.

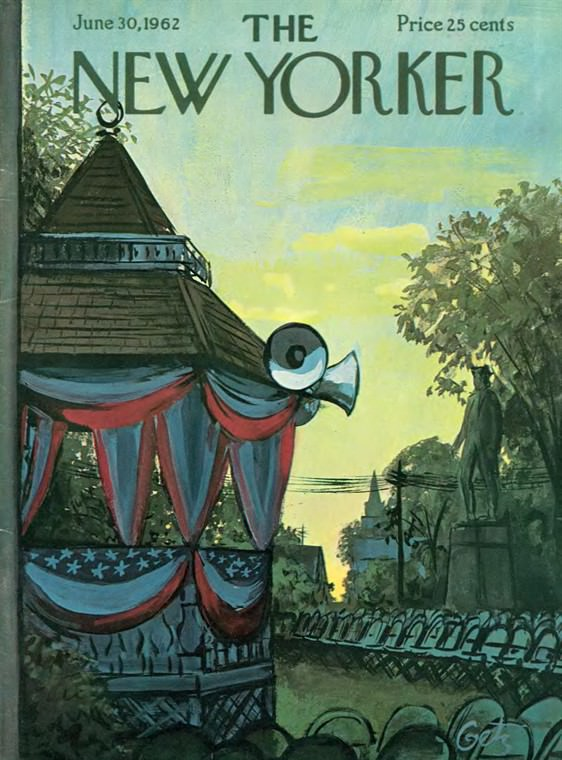

Silent Spring serialised in The New Yorker magazine in 1962 - this assured national readership for the Environmentalist message and impacted on Sixties youth culture. By the end of the decade we had created The Whole Earth Catalog (Stewart Brand 1968), Friends of the Earth (1969) and GreenPeace (1971)...

(from Bob Cotton's mediainspiratorium)

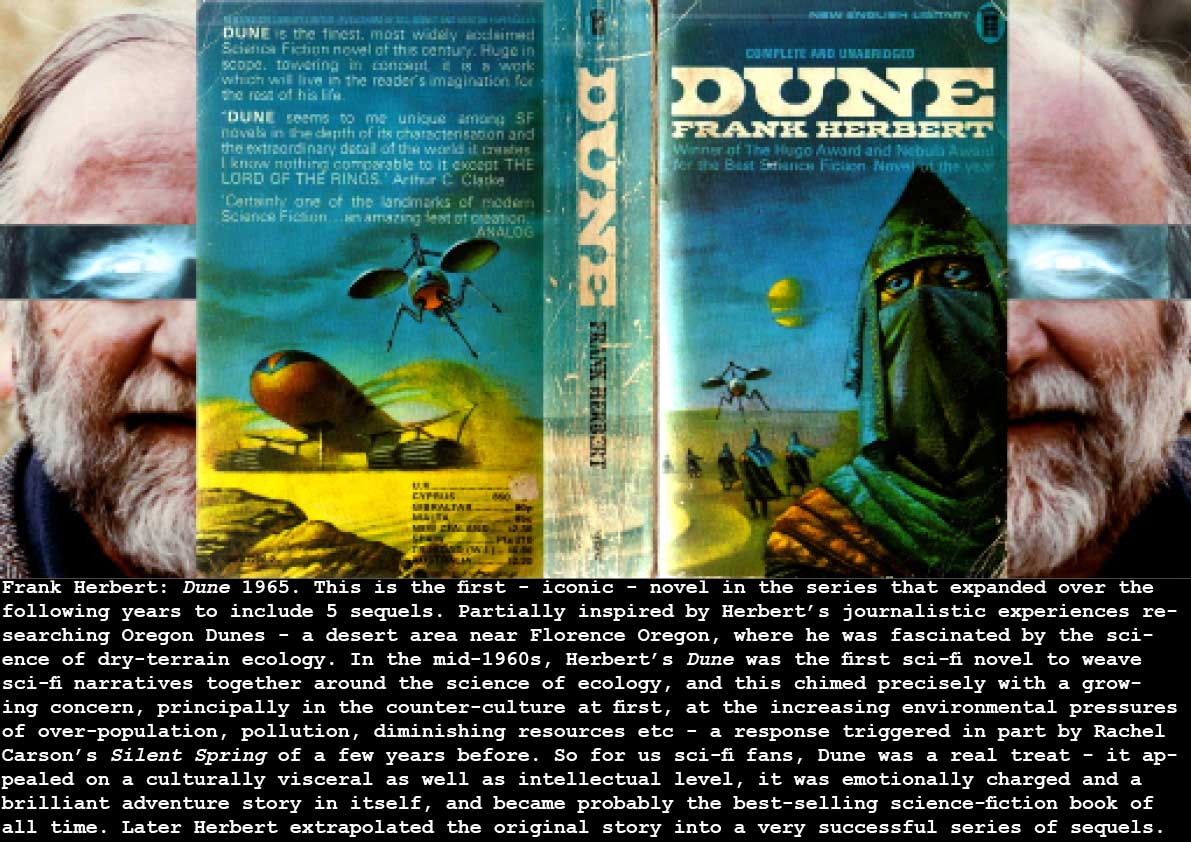

Following Rachel Carson's brilliant analyses and cri de coeur in Silent Spring (1963), 'ecology' and the environment increasingly became a core topic n science and in the 'underground' (counter-culture) of the mid-Sixties, and Frank Herbert brought this topic into the decisive core of his science-fiction space opera Dune in 1965. Herbert's character Kynes in Dune is described as the Imperial Planetary Ecologist, but what he isn't reporting to the Emperor is that he is helping to foment a large, popular underground rising of Dune natives, who, hidden in the Desert are developing a sophisticated ecological understanding of how the desert-planet works, and how the giant worms have evolved and how they can be controlled...

Herbert's Dune was a literary and commercial success - one of the most successful in the genre, and together with Walter Tevis' brilliant The Man Who fell to Earth (1963) set the tone for intellectually satisfying cult sci-fi in the early-mid-Sixties.

Stan Lee (plotter/producer) + Jack Kirby (artist): Marvel Comics: Thor comic c1966

I fell in love with Marvel Comics in the early Sixties, and especially their version of the Norse legends in Thor (and later Barry Smith's re-evocation of a fantasy dark ages in Conan the Barbarian). I loved Kirby's cinematic drawing - his exagerrated perspective, his ability to create the kind of panoramic overviews like that above.

This was important also for those youngsters less acquainted with the history of myth and religion, including Norse mythology and the wonderful world-view associated with Bifrost, the rainbow bridge, Yggdrasil the World Tree, Odin, Loki, Freya, the World Serpent - even the mythographic relationship between Odin - the Tree - and Christ on the wooden cross:

"...the Eddic World Ash, Yggdrasil, whose shaft was the pivot of the revolving heavens, with the World Eagle perched on its summit, four stags running amongst its branches, browsing on its leaves, and the Cosmic Serpent gnawing at its root:

The ash Yggdrasil suffers anguish,

More than men can know:

The stag bites above, on the side it rots;

And the Dragon gnaws from beneath.

It is the greatest of all trees and the best, the ash where the Gods give judgement every day. Its limbs spread over the world, and stand above heaven. Its roots penetrate the abyss. And its name, Yggdrasil, means 'The horse of Odin' whose other name is Odin; for this great god once hung upon that tree for nine days, in the way of a sacrifice to himself." (Campbell: Primitive Mythology 1959 page 120-121)

Yggdrasil AI prompt: Yggdrasil tree, nordic mythology theme, enormous, gigantic, lively, naturally, a little mystery OpenArt SDXL

Yggdrasil AI prompt: Yggdrasil tree, nordic mythology theme, enormous, gigantic, lively, naturally, a little mystery OpenArt SDXL

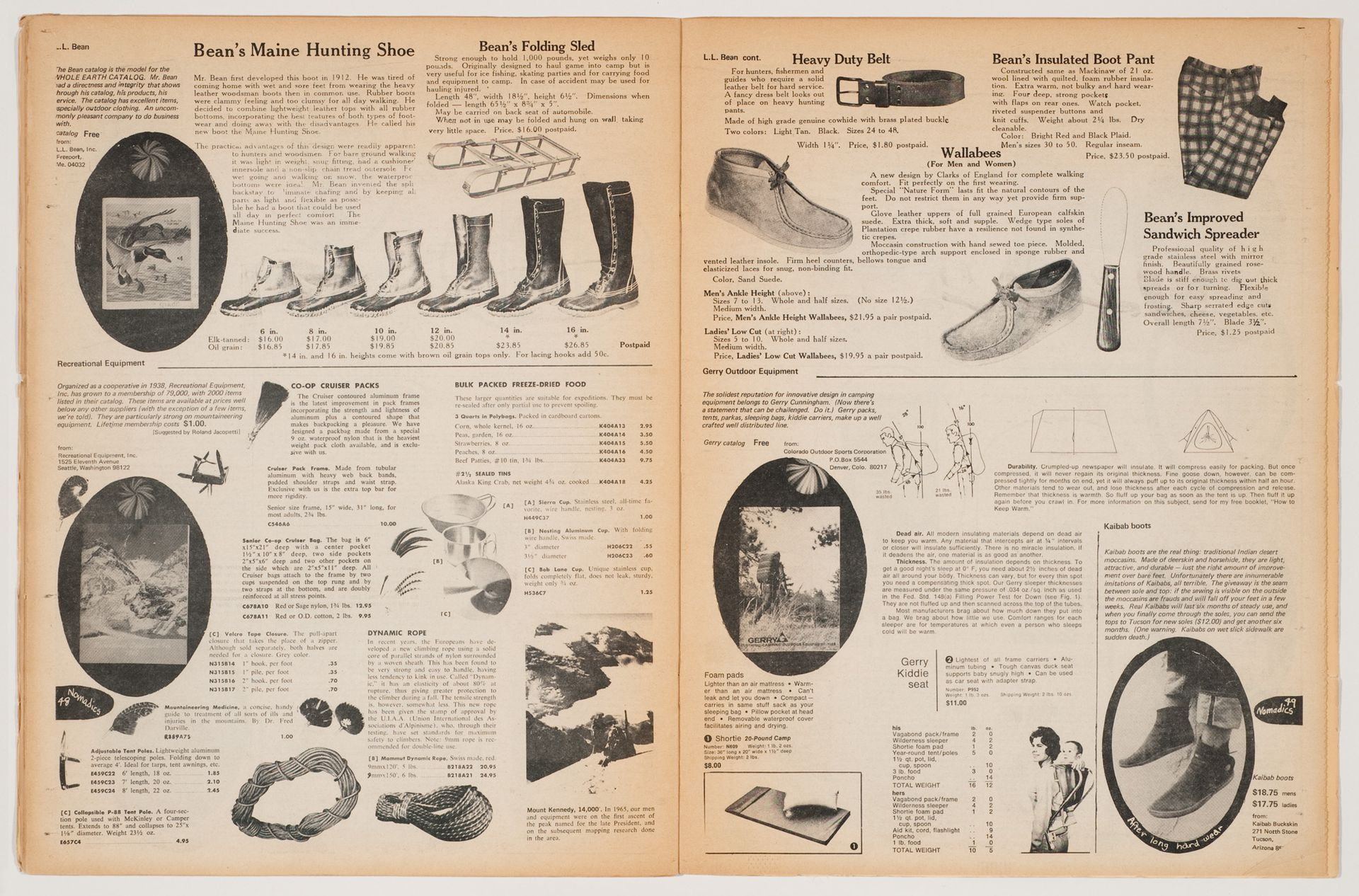

Stewart Brand: Whole Earth Catalog 1968. Stewart Brand's inspired publication - the bible of the counter-culture in the late Sixties and now still totally relevant to the pending environmental disaster of the 21st century - was a work of genius that grew, bottom-up, from Brand's evangelising environmental concerns and relevant products in his Whole Earth Truck Store a truck from which he sold books, tools and news around pop festivals, folk-clubs, cafes and other 'underground' venues in the late 1960s. Inspired by the first photographs of the whole Earth (from c1966-67) Brand built a mail-order catalogue that was wildly successful in reaching into the zeitgeist of the counter-culture - striking a chord with me and millions of others of my baby-boomer generation (I was born in 1945) and succeeding in spreading an educational web for us to explore and to comment upon - literally a paper version of the WWW some 30 or so years before Berners Lee starting tinkering so brilliantly with hypertext. WEC was dedicated to Richard Buckminster Fuller who had developed his ideas of Doing More with Less and

Stewart Brand: Whole Earth Catalog 1968. Stewart Brand's inspired publication - the bible of the counter-culture in the late Sixties and now still totally relevant to the pending environmental disaster of the 21st century - was a work of genius that grew, bottom-up, from Brand's evangelising environmental concerns and relevant products in his Whole Earth Truck Store a truck from which he sold books, tools and news around pop festivals, folk-clubs, cafes and other 'underground' venues in the late 1960s. Inspired by the first photographs of the whole Earth (from c1966-67) Brand built a mail-order catalogue that was wildly successful in reaching into the zeitgeist of the counter-culture - striking a chord with me and millions of others of my baby-boomer generation (I was born in 1945) and succeeding in spreading an educational web for us to explore and to comment upon - literally a paper version of the WWW some 30 or so years before Berners Lee starting tinkering so brilliantly with hypertext. WEC was dedicated to Richard Buckminster Fuller who had developed his ideas of Doing More with Less and Synergy, and his World Resources inventory and World-Game from the early Sixties and who inspired the baby-boomer generation and counter-culture alike.

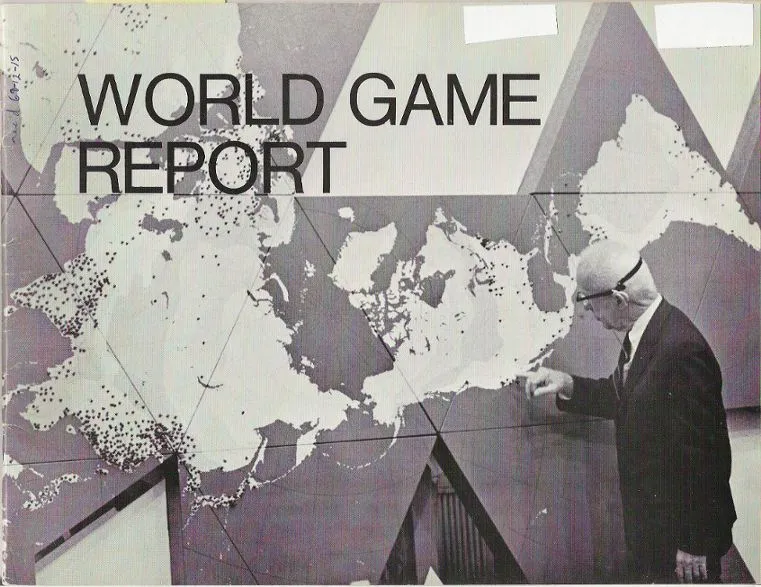

Fuller's sketch of his idea for a 200ft diameter geosphere suspended over Manhattan - such 'geospheres' would be studded with light-bulbs (think nowadays of LEDs) and programmed to display images and stats to illustrate the 'geostatistics' recording the arguments of competing individuals, scientists of various specialisms, teams, parties etc for how to make the world work for everyone on the planet without disadvantaging anyone... or for how to achieve the bare maximum for everyone... The geosphere displays would keep everyone up-to-date, and be a constant reminder, in impressive symbolism, of the state of the planet...

(from Bob Cotton's mediainspiratorium)

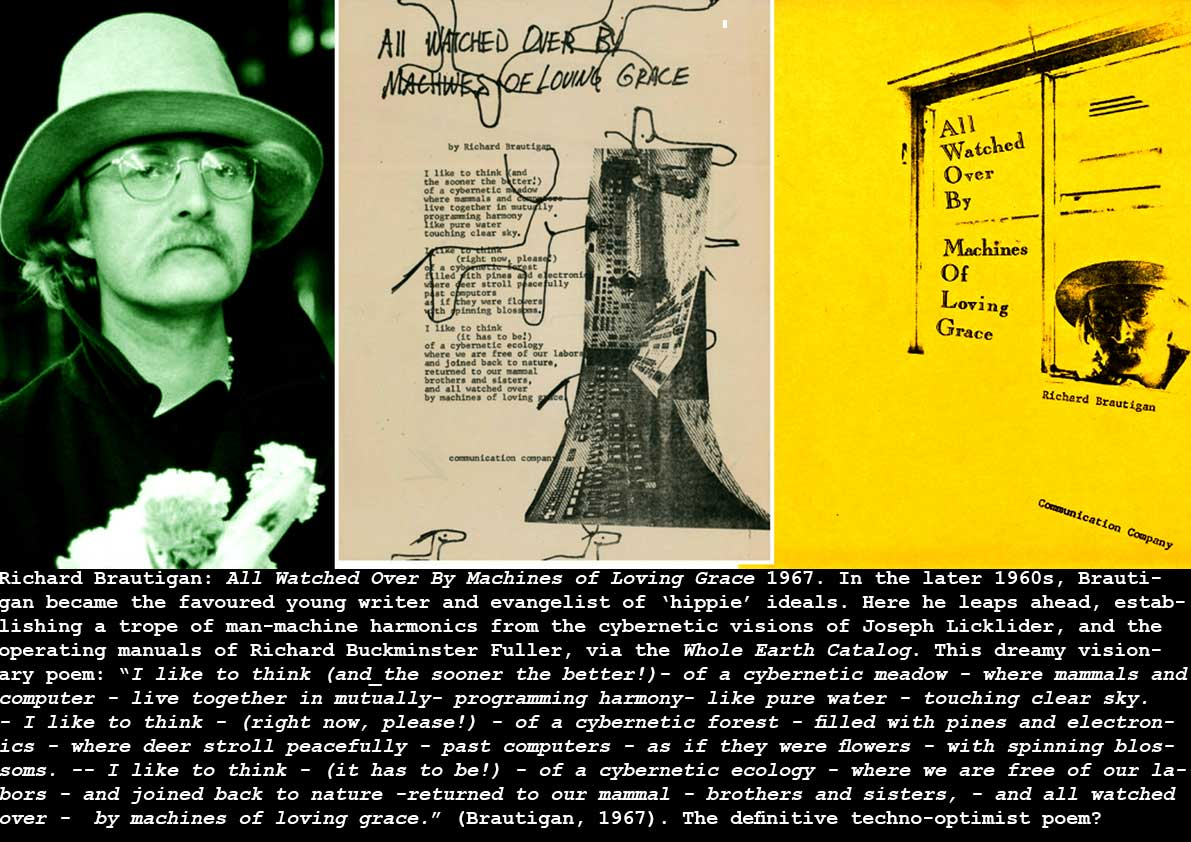

"This is an intriguing poem for it’s time. For a start, we were in the middle of a mind-numbingly frightening Cold War in which the very technologies praised by Brautigan were generally considered by the young to be the avatars or tools of the threatening Military-Industrial Complex. The potential benefits of ‘personal’ computing were only just being glimpsed by a tiny few engineer-visionaries like Joseph (JCR) Licklider, Douglas Engelbart, Ted Nelson and Alan Kay. The ubiquitous computing/sensing environment imagined by Brautigan is still 40 years away – there was no web, no personal computer, no internet, no cellular – even the germinal ideas for these epoch-changing technologies were only shared by a tiny, tiny few. So for a 32-year old dreamy hippie novelist and poet – then really only known for his first novel A Confederate General from Big Sur (1964) to suddenly find himself in company with the leading-edge engineer-visionaries of DARPA (just at this period solving some of the issues relating to an internetwork linking computers at the main universities and research centres in the USA); and on the other subject of the poem (ecology-environment), even this was only just recently au courant – Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring only 5 years previously, Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth – even the Whole Earth Catalog – still in the future. So that’s what I mean about intriguing – this is a completely anachronistic glimpse of the kind of visions that were inspiring Jim Haynes (Arts Lab 1967), Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog (1968), and Richard Buckminster Fuller: Geoscope World Game (1962) – a utopian vision of man-machine harmony… The philosopher-critic Theodore Roszak was to examine these issues/tautologies in much greater depth over the next few years – in books like The Making of a Counter Culture 1969, and Where the Wasteland Ends (1971) , and over a decade later Stewart Brand would begin to publish The Whole Earth Software Catalog (1984), though he had, presciently, included some coverage of cybernetics and programming - and Systems Theory - in the Whole Earth Catalog and its seasonal supplements (1968-69). Fred Turner’s historical analysis of this period and this topic: From Counterculture to Cyberculture (2006) is recommended. But Brautigan's poem is the proof that he danced with the spirit of the age…" (bob cotton in https://mediainspiratorium.com 1960-1970)

Stuart Kauffman: At Home in the Universe : The search for laws of Self-organisation and Complexity 1995

As systems theory focused more upon the mysteries of chaos theory, complexity and self-organisation in the 1990s, Complexity Theory became a major focus: and Stuart Kauffman - a professor and spokesperson of the prestigious Sante Fe Institute has written the best books on this, including as well as The Origins of Order (1993)

"Complexity theory is one of the most controversial areas of current scientific research. Developing out of chaos theory, complexity suggests that there are hidden tendencies in nature to select ordered states, even when statistically they are vastly outnumbered by chaotic possibilities: that there is a deep natural impulse towards order, counteracting the degenerative tendencies of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Like chaos, complexity is a multidisciplinary area of research and those involved include physicists, economists and biologists. This is a study of complexity." (Amazon book summary)

Stewart Brand: The Next Whole Earth Catalog 1980

Robert Axelrod: The Evolution of Cooperation 1984

"This basic problem occurs when the pursuit of self-interest by each leads to a poor outcome for all. To understand the vast array of specific situations like this, we need a way to represent what is common to them without becoming bogged down in the details unique to each. Fortunately, there is such representation available: the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma game, invented about 1950 by two Rand Corporation scientists. In this game there are two players. Each has two choices, namely “cooperate” or “defect.” The game is called the Prisoner’s Dilemma because in its original form two prisoners face the choice of informing on each other (defecting) or remaining silent (cooperating). Each must make the choice without knowing what the other will do. One form of the game pays off as follows: Player’s Choice Payoff If both players defect: Both players get $1. If both players cooperate: Both players get $3. If one player defects while The defector gets $5 and the other player cooperates: the cooperator gets zero. One can see that no matter what the other player does, defection yields a higher payoff than cooperation. If you think the other player will cooperate, it pays for you to defect (getting $5 rather than $3). On the other hand, if you think the other player will defect, it still pays for you to defect (getting $1 rather than zero). Therefore the temptation is to defect. But, the dilemma is that if both defect, both do worse than if both had cooperated. To find a good strategy to use in such situations, I invited experts in game theory to submit programs for a computer Prisoner’s Dilemma tournament – much like a computer chess tournament. Each of these strategies was paired off with each of the others to see which would do best overall in repeated interactions. Amazingly enough, the winner was the simplest of all candidates submitted. This was a strategy of simple reciprocity which cooperates on the first move and then does whatever the other player did on the previous move. Using an American colloquial phrase, this strategy was named Tit for Tat. A second round of the tournament was conducted in which many more entries were submitted by amateurs and professionals alike, all of whom were aware of the results of the first round. The result was another victory for simple reciprocity." (Stanford University)

In retrospect, Tit for Tat proved to be the essential primordial rule for survival - a point argued by John and Mary Gribben in their Being Human: Putting People in an Evolutionary Perspective 1993 - the 'rule' adopted by strangers meeting each other - its properly called reciprocal altruism.

Lynn Margulis: Symbiotic Planet (A New Look at Evolution) 1999

"In particular, Margulis incorporated symbiosis as an evolutionary force by developing another theory, that of serial endosymbiosis or symbiogenesis, which had already been proposed a century ago by some voices without much success. This theory took up Darwin's natural selection and defended that cooperation and association also allow life to make evolutionary leaps. Most of Margulis' postulates proved to be true at the end of the 1970s, but the theory of endosymbiosis is still largely unknown to most people."

"Although Charles Darwin's theory of evolution laid the foundations of modern biology, it did not tell the whole story. Most remarkably, The Origin of Species said very little about, of all things, the origins of species. Darwin and his modern successors have shown very convincingly how inherited variations are naturally selected, but they leave unanswered how variant organisms come to be in the first place.In Symbiotic Planet, renowned scientist Lynn Margulis shows that symbiosis, which simply means members of different species living in physical contact with each other, is crucial to the origins of evolutionary novelty. Ranging from bacteria, the smallest kinds of life, to the largest,the living Earth itself,Margulis explains the symbiotic origins of many of evolution's most important innovations. The very cells we're made of started as symbiotic unions of different kinds of bacteria. Sex,and its inevitable corollary, death,arose when failed attempts at cannibalism resulted in seasonally repeated mergers of some of our tiniest ancestors. Dry land became forested only after symbioses of algae and fungi evolved into plants. Since all living things are bathed by the same waters and atmosphere, all the inhabitants of Earth belong to a symbiotic union. Gaia, the finely tuned largest ecosystem of the Earth's surface, is just symbiosis as seen from space. Along the way, Margulis describes her initiation into the world of science and the early steps in the present revolution in evolutionary biology the importance of species classification for how we think about the living world and the way academic apartheid" can block scientific advancement. Written with enthusiasm and authority, this is a book that could change the way you view our living Earth." (Amazon book description)

Margulis' main argument is that symbiogenesis was the most important mechanism in evolution - we are the product not of 'nature raw in tooth and claw', but of mutual aid, cooperation and collaboration. Margulis partnered with James Lovelock on their important Gaia theory - that the world is itself a self-organising system or living organism that mankind is threatening...

Extinction Rebellion 2018

Extinction Rebellion 2018